My last post addressed my approach to making the 80-odd different poets in my book sound different from each other by adjusting form, diction, and syntax / register. What happens, though, when you have four different poets all using the same stanza form? Here I look specifically at different approaches to rhyme in Alcaeus, Sappho, Catullus and Horace.

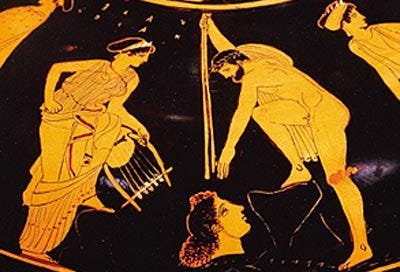

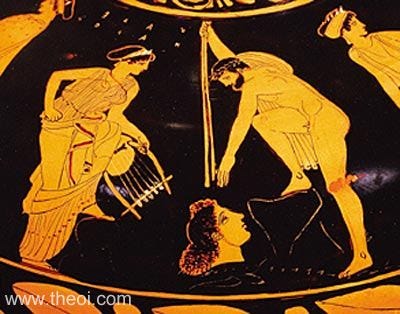

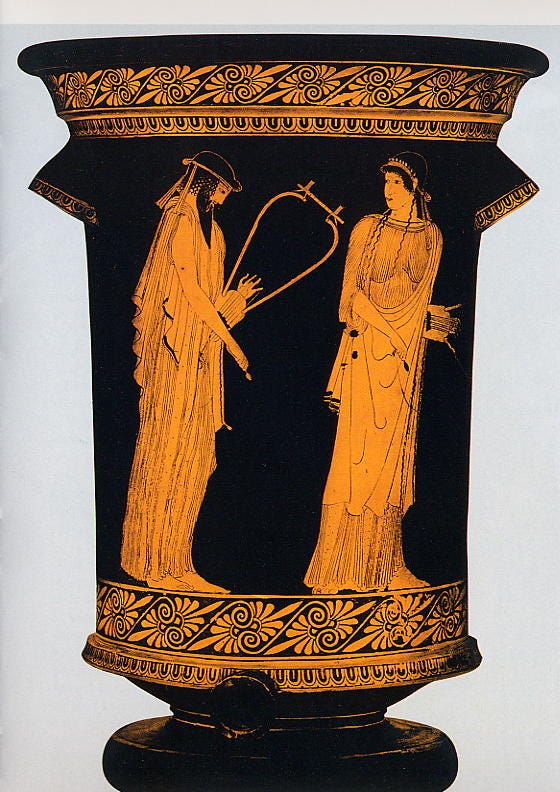

Arion’s was not the only lyre to make landfall on a musical shore—centuries before, the lyre of Orpheus had washed up on the island of Lesbos, along, of course, with his severed head, still singing, as when carried by the Thracian river Hebrus out to sea. In this way Lesbos, blessed by the arch-poet’s relics, became the first capital of Greek lyric song. Here is a hymn by Alcaeus of Mytilene, one of the beneficiaries of that tradition:

δεῦτέ μοι νᾶσον Πέλοπος λίποντες,

παῖδες ἴφθιμοι Δίος ἠδὲ Λήδας,

εὐνόωι θύμωι προφάνητε Κάστορ

καὶ Πολύδευκες⋅οἳ κὰτ᾽ εὔρηαν χθόνα καὶ θάλασσαν

παῖσαν ἔρχεσθ᾽ ὠκυπόδων ἐπ᾽ ἴππων,

ῤήα δ᾽ ἀνθρώποις θανάτω ῤύεσθε

ζακρυόεντοςεὐσδύγων θρώισκοντ[ες . . ] ἄκρα νάων

πήλοθεν λάμπροι προ[ ]τρ[ . . . . ]ντες

ἀργαλέαι δ᾽ ἐν νύκτι φάος φέροντες

νᾶϊ μελαίναι⋅Leave the island where Pelops once was master,

o Leda’s powerful progeny, and Zeus’s;

to me here now appear and look kindly, Castor

and Polydeuces,you who, astride your horses, galloping, whizzing,

crisscross the whole of the sea and the wide earth,

and easily rescue people from the freezing

clutches of death,leaping through crow’s-nests, high over rowers pulling,

flickering forestays, distantly radiant,

to the black ship in its night of trial revealing

your corposant

Alcaeus’ poem is in sapphics, a stanza most closely associated with his mellifluous contemporary, Sappho, which has a certain prominence in classical lyric, being used by four of its chief proponents: in addition to Sappho and Alcaeus, the Romans Catullus and Horace. My book renders the classical meter of all four poets into the same English stanza: a quatrain rhyming abab where the first three lines are pentameter and the last is dimeter. The stanza is an interesting test case for difference of voice within sameness of form; the challenge it presents the sedulous mockingbird is to convey the familial strophic resemblance between poems while still imbuing each poet with a distinctive voice and personality.

Here’s a poem by Sappho in her eponymous stanza, probably her most famous (you can hear my translation read by Major Jackson on The Slowdown, here):

φαίνεταί μοι κῆνος ἴσος θέοισιν

ἔμμεν᾽ ὤνηρ, ὄττις ἐνάντιός τοι

ἰσδάνει καὶ πλάσιον ἆδυ φωνεί-

σας ὐπακούεικαὶ γελαίσας ἰμέροεν, τό μ᾽ ἦ μὰν

καρδίαν ἐν στήθεσιν ἐπτόαισεν·

ὠς γὰρ ἔς σ᾽ ἴδω βρόχε᾽, ὤς με φώναι-

σ᾽ οὐδ᾽ ἒν ἔτ᾽ εἴκει,

ἀλλ᾽ ἄκαν μὲν γλῶσσα †ἔαγε†, λέπτον

δ᾽ αὔτικα χρῶι πῦρ ὐπαδεδρόμηκεν,

ὀππάτεσσι δ᾽ οὐδ᾽ ἒν ὄρημμ᾽, ἐπιρρόμ-

βεισι δ᾽ ἄκουαι,

†έκαδε μ᾽ ἴδρως ψῦχρος κακχέεται†, τρόμος δὲ

παῖσαν ἄγρει, χλωροτέρα δὲ ποίας

ἔμμι, τεθνάκην δ᾽ ὀλίγω ᾽πιδεύης

φαίνομ᾽ ἔμ᾽ αὔταHe seems like the gods’ equal, that man, who

ever he is, who takes his seat so close

across from you, and listens raptly to

your lilting voiceand lovely laughter, which, as it wafts by,

sets the heart in my ribcage fluttering;

as soon as I glance at you a moment, I

can’t say a thing,and my tongue stiffens into silence, thin

flames underneath my skin prickle and spark,

a rush of blood booms in my ears, and then

my eyes go dark,and sweat pours coldly over me, and all

my body shakes, suddenly sallower

than summer grass, and death, I fear and feel,

is very near.

Sappho’s poem is famous for a lot of reasons, including the rhapsody of pseudo-Longinus, who quotes it in full: ‘Are you not amazed how at one instant she summons, as though they were all alien from herself and dispersed, soul, body, ears, tongue, eyes, colour?’

I hope that if you compare Sappho’s poem with Alcaeus’ above you’ll hear the translation making a more rackety sort of noise in the Alcaeus, with louder rhymes, whether slant or full, like ‘master / Castor,’ ‘whizzing / freezing,’ and a higher emphasis on verbs and participles. By contrast, rhymes like ‘all / feel’ or ‘thin / then’ in Sappho are so light you hardly hear them as such. In addition, rhymes like ‘thing / fluttering’ and ‘sallower / near’ pair a secondary stress against a primary, to achieve a muffled, understated effect.

Yet I also hope there are some similarities between these two Greek poets which, in turn, contrast with the two Latin ones below. In both Greek poems I use quite a few off-rhymes—about 50/50 with full rhymes. On the Lévi-Strauss continuum between raw and cooked, the Greeks strike me as more raw, the Romans more cooked. In general, I feel these kinds of off-rhymes convey ‘rawness,’ but try to avoid them in more studied poets. (Though I also have a bit of a sweet tooth for certain kinds of disyllabic off-rhymes, like glamor / summer, or traces / kisses, which no doubt I overuse.)

To see what I mean, compare the handling of rhyme in the Sappho translation above with my translation of Catullus’s translation of Sappho:

Ille mi par esse deo videtur,

ille, si fas est, superare divos,

qui sedens adversus identidem te

spectat et auditdulce ridentem, misero quod omnis

eripit sensus mihi: nam simul te,

Lesbia, aspexi, nihil est super mi

vocis in ore,lingua sed torpet, tenuis sub artus

flamma demanat, sonitu suopte

tintinant aures gemina, teguntur

lumina nocte.otium, Catulle, tibi molestum est:

otio exsultas nimiumque gestis:

otium et reges prius et beatas

perdidit urbes.The equal of a god that man appears,

better than gods, if it’s not blasphemy,

who sits across from you, and stares, and hears

continuallyyour lovely laughter, which, in my despair,

siphons my senses; soon as I look upon

you, Lesbia, I’m dumb, and don’t know where

my voice has gone;my tongue grows heavy, underneath my skin

a thin flame drips, my ears ring with a bright

and tinny sound, and my eyes are veiled within

a two-fold night.Free time, Catullus, that’s what’s killing you!

Free time fuels your fidgeting and your flings.

Free time has leveled prosperous cities, too,

and mighty kings.

To my ear Sappho’s Aeolic has always sounded lighter and airier than Catullus’ Latin, which is laborious by comparison. The Greek is all open vowels and melisma (there is something vaguely luscinine about it), while the Latin hews and hoists words like marble slabs in a monumental bathhouse. At any rate, in these two translations, while the content of each poem is much the same, the approach to rhyming is quite different. In Catullus, rhymes are masculine (monosyllabic, mostly stressed) and full, while the Sappho uses off-rhymes (close/voice, thin/then, all/feel), rhymes of secondary with primary stresses (fluttering / thing, sallower / near), and open vowels (who / to, I / by), which combine with the enjambment for a much lighter effect. In addition, though each long line has five stresses, more of these are light metrical (that is, promoted) stresses in Sappho than in Catullus, where most of the lines are heavily ‘correct.’ There are, of course, other differences between the two poems—most notably Catullus’ final stanza, which has nothing to do with Sappho’s poem—but as this is a mere flyover I shall proceed to Horace and his famous ‘integer vitae’ (Ode I.21):

Integer vitae scelerisque purus

non eget Mauris iaculis neque arcu

nec venenatis gravida sagittis,

Fusce, pharetra,sive per Syrtis iter aestuosas

sive facturus per inhospitalem

Caucasum vel quae loca fabulosus

lambit Hydaspes.Namque me silva lupus in Sabina,

dum meam canto Lalagen et ultra

terminum curis vagor expeditis,

fugit inermem,quale portentum neque militaris

Daunias latis alit aesculetis

nec Iubae tellus generat, leonum

arida nutrix.Pone me pigris ubi nulla campis

arbor aestiva recreatur aura,

quod latus mundi nebulae malusque

Iuppiter urget;pone sub curru nimium propinqui

solis in terra domibus negata:

dulce ridentem Lalagen amabo,

dulce loquentem.A man whose life is whole, whose heart is clean,

Fuscus, does not need Moorish spears to seize on,

or bows, or quivers of arrows that have been

tipped with poison,not if he makes for Libya’s sweltering sands,

or for the Caucasus, where wind whiplashes

the hostile peaks, or for the fabled lands

the Indus washes.The proof? A wolf, as I wandered wholly charmed

by Lalage, singing of her and lost in thought

out through my Sabine woods, though I was unarmed,

took off like a shot;a prodigy like Apulia never spied

among its oaks and bellicose environs;

nor has Numidia, that baked and dried

nursemaid of lions.Take me to fields that sluggish ice sheets cover,

which no trees break, no summer weather warms,

some region Jupiter’s knitted brow scowls over

with constant storms;take me to where the sun swoops lower, faster,

so low there are no towns or houses built;

I’ll still love Lalage for her lovely laughter,

her lovely lilt.

While Catullus is genuinely tormented — partly by his toxic relationship, partly by his failure to live up to ideals of Romanitas — Horace is ludic. One doesn’t for a minute imagine that he believes the elegiac commonplace he articulates here, that lovers are shielded by their love from hostile encounters in inhospitable climes; rather, he would say with Hemingway’s Jake Barnes, “Isn’t it pretty to think so?” It’s also pretty to say so, at least in this language. In the poem, which uses the Sapphic meter Catullus first introduced into Latin, Horace quotes Catullus quoting Sappho (dulce ridentem, “lovely laughter” for Sappho’s gelaisas imeroen), but he also corrects Catullus’s version, restoring in his last line (dulce loquentem, here rendered as ‘lovely lilt’) Sappho’s adu phoneisas, which Catullus’ version omits. Horace thus assimilates both his grandiose elegiac claims and his winking references to Catullus and Sappho into the beautiful babble of poetry, which he represents in the form of “Lalage,” Greek for “babbler.” Like Lalage, poetry is a babbler Horace loves but does not take too seriously. In my translation, the combination of perfect masculine rhymes with fairly loud, slightly comic feminine off-rhymes (seize on / poison; environs / lions) tries for something of Horace’s playful confidence, and the self-consciously literary game he is playing.

I hope these three translations, taken together, suggest, with their varying approaches to rhyme (as well as sound and diction), something of the different spirits of these three poets, while also preserving their sapphic family resemblances.