An Irish Elegist Foresees His Death

Propertius & Michael Longley: "Here's how I want my funeral to go"

“What is love but a strange light falling between two individuals? In high poetry the words have relationships with each other, and on various planes: there are counterpoints of meaning, sound, cadence, pace and tone. The chemistry, the relationship, the magic, the mystery — call it what you will — is there and it is inexplicable. From this confusion, let us say that in high poetry the words love each other.” — Michael Longley, “Sextus Propertius,” 1962

The Irish poet Michael Longley died last week. As both poet and classicist he was the genuine article and is best known for his adaptations of Homeric scenes into short, spare lyric poems; his most famous, “Ceasefire,” invokes the truce between Priam and Achilles in Iliad 24 in the context of the cease-fire declared by the IRA in 1994 (and no doubt finds new resonance today). In this he used not so much the discipline of form as the distance of Classics as (in the metaphor of Adrienne Rich) “asbestos gloves” to address what was otherwise too hot to handle.

Homer aside, Longley was also an accomplished love poet whose engagement with the Latin love elegists began early—a deeply impressive reflection on Propertius, written at only 22 or 3, is one of the earliest essays in Sidelines: Selected Prose 1962-2015. His short poem “Love Poet” (from New Poems, 1979-84) seems an apt (albeit stern) commentary on the self-aggrandizing indecency and metaphorical murderousness of transforming a loved person into art—in Propertius’ case, Cynthia; in his own, the literary critic Edna Longley, his wife of more than 60 years (!):

Love Poet

I make my peace with murderers.

I lock pubic hair from victims

In an airtight tin, mummify

Angel feathers, tobacco shreds.All that survives my acid bath

Is a solitary gall-stone

Like a pebble out on mud flats

Or the ghost of an avocado.

In his Propertius essay, Longley recommends lightly rhymed ABBA quatrains to render Latin elegiac couplets; I discuss my own differing approach here, but would love to see his envelope quatrains if he ever produced any! Besides this suggestion his brief paper contains a number of highly lucid and suggestive observations, which I’ll discuss in the context of an excerpt from elegy 2.13.

from Propertius 2.13 (ll. 17-42)

QVANDOCVMQVE igitur nostros mors claudet ocellos,

accipe quae serves funeris acta mei.

nec mea tunc longa spatietur imagine pompa

nec tuba sit fati vana querela mei;

nec mihi tunc fulcro sternatur lectus eburno,

nec sit in Attalico mors mea nixa toro.

desit odoriferis ordo mihi lancibus, adsint

plebei parvae funeris exsequiae.sat mea sat magna est, si tres sint pompa libelli,

quos ego Persephonae maxima dona feram.

tu vero nudum pectus lacerata sequeris,

nec fueris nomen lassa vocare meum,

osculaque in gelidis pones suprema labellis,

cum dabitur Syrio munere plenus onyx.

deinde, ubi suppositus cinerem me fecerit ardor

accipiat Manis parvula testa meos,

et sit in exiguo laurus super addita busto,

quae tegat exstincti funeris umbra locum,

et duo sint versus: QVI NVNC IACET HORRIDA PVLVIS,

VNIVS HIC QVONDAM SERVVS AMORIS ERAT.nec minus haec nostri notescet fama sepulcri,

quam fuerant Pthii busta cruenta viri.

tu quoque si quando venies ad fata, memento,

hoc iter ad lapides cana veni memores.

interea cave sis nos aspernata sepultos:

non nihil ad verum conscia terra sapit.

Therefore, when Death at last takes me below,

here’s how I want my funeral to go:

I’ll have no lines of wax masks on parade,

no trumpet notes of empty sorrow played, 20

no ivory posts to trundle my bier with,

no cloth of gold to spread beneath my death,

no dishes of rare incense—just the small

observances of humble burial.

My three books will be ample obsequy—

my true pride, gifts I’ll give Persephone.

You follow, breasts laid bare to lacerations,

unwearied by my name’s reiterations,

and plant last kisses on my frigid lips

when the scent-box’s Syrian offering tips. 30

And when I’m ash the heat no longer roasts,

then let a little vessel be my ghost’s,

and plant a laurel over my small stone,

to shade the spot where fire scoured bone,

and write: “Here lie the loathsome remnants of

one who enslaved himself to one sole love.”

Yet my tomb’s fame will ripple and endure

like that of Phthia’s blood-stained sepulchre.

You, when death’s nearing, don’t forget the way,

but come; these stones will know you, with the gray. 40

See that you don’t offend my dust. Beware:

the earth knows what it knows, and truth is there.

Propertius often employs a form of callida iunctura in which adjectives which grammatically agree with one noun are made to do double duty through their proximity to another. This may be in part what Michael Longley means when he points to the use of “soft” and “loud” words in the pentameters, and suggests that the latter diffuse their influence over the former. Here, I might suggest the way vana querela (vain complaint, empty lament) in the fourth line above resonates surrounded by fati mei (my fate), or how lassa (wearied) touches nomen (my name), or how in the penultimate couplet above, cana (grey, hoary) touches lapides (stones) but agrees grammatically with the subject of veni (come!), while memores (remembering, memorious) agrees grammatically with ‘stones’ but also touches the ‘you’ of veni. “Come, remembering, to my gray stones” is a sort of shadow meaning of what Propertius actually says, “Come, when you’re gray, to my remembering stones.” What exactly the stones remember—me, or you, or something unspoken between us—is not specified, though my translation makes a choice.

Longley made two other extremely salient observations. In distinguishing Propertius from his two fellow love elegists, Ovid and Tibullus, he articulates well something I had perceived but hadn’t quite put my finger on: that Propertius’ pentameters tend to reinforce his hexameters, creating a harmonious effect, while Ovid and Tibullus more often use the pentameter as a mirror, creating antiphony. That approach is very much in evidence in the present passage. Finally, Longley suggests that Propertius uses a richer vocabulary in his first two books, while his latter two show an increasing perfection of form, as evidenced by the much more consistent use of disyllabic words which end each pentameter, as opposed to the much more frequent use of three- and four-syllable words in the first two books. The present example, from Book 2, bears up this observation, with the fourth couplet ending in “exsequiae” and the twelfth “memores.” According to Longley, “had [Propertius] lived to write more, it is likely that he would have combined the richness of his early work with the deeper control and co-ordination of Book IV.”

Another elegy of Propertius, from Book 3, further confirms the justice of Longley’s observations. This one is, as Longley suggests, closer to the manner of Ovid’s Amores than Propertius’ first two books. It does not take off, like many Propertian elegies, from the “hidden standpoint” which can make his turns of thought so hard to follow; rather, as in the Amores, we get a concrete situation: the poet has received a midnight summons from his mistress, which makes him nervous, since the journey could be dangerous; Rome had no police and traveling alone at night was a risky business. Also as in Ovid, the poem’s thought is organized into three clear stanzas, or movements: the first decad presents the conundrum, and the second two offer different arguments in favor of accepting the risk. Neither of them is especially persuasive: the first gives memorable statement to a common elegiac trope, also found in Tibullus and (perhaps parodically) in Horace, that love surrounds the lover with a kind of divine forcefield, while in the second the poet tries to convince himself that death in the service of love would be a good thing, and fondly imagines his funeral. Thus the poem also offers a kind of dialectical movement: it asserts the possibility of death, then denies it, then embraces it. Propertius does not, however, as I think Ovid would have, resolve the initial conundrum and clarify what action he decided to take; the poem eschews ring composition to leave us in a very different place from where we began. At any rate I think it is eminently fair to regard this poem as more formally polished but less lexically interesting than the above excerpt from Book 2; and note as well that every pentameter ends with a disyllable.

3.16

Nox media, et dominae mihi venit epistula nostrae:

Tibure me missa iussit adesse mora,

candida qua geminas ostendunt culmina turres,

et cadit in patulos nympha Aniena lacus.

quid faciam? obductis committam mene tenebris

ut timeam audacis in mea membra manus?

at si distulero haec nostro mandata timore,

nocturno fletus saevior hoste mihi.

peccaram semel, et totum sum pulsus in annum:

in me mansuetas non habet illa manus.

nec tamen est quisquam, sacros qui laedat amantes:

Scironis medias his licet ire vias.

quisquis amator erit, Scythicis licet ambulet oris,

nemo adeo ut feriat barbarus esse volet.

sanguine tam parvo quis enim spargatur amantis

improbus, et cuius sit comes ipsa Venus?

luna ministrat iter, demonstrant astra salebras,

ipse Amor accensas praecutit ante faces,

saeva canum rabies morsus avertit hiantis:

huic generi quovis tempore tuta viast.

quod si certa meos sequerentur funera cursus,

tali mors pretio vel sit emenda mihi.

afferet haec unguenta mihi sertisque sepulcrum

ornabit custos ad mea busta sedens.

di faciant, mea ne terra locet ossa frequenti

qua facit assiduo tramite vulgus iter!

post mortem tumuli sic infamantur amantum.

me tegat arborea devia terra coma,

aut humer ignotae cumulis vallatus harenae:

non iuvat in media nomen habere via.

The dead of night. A letter comes to me:

she orders me to Tibur, instantly.

That’s Tibur, where the cliffsides whitely flash

and down into pools the Anio’s falls crash.

What should I do? Ignore the dark, depart,

hope criminals can’t hear my pounding heart?

But say I don’t heed her, but heed my fears:

no criminal could be scarier than her tears.

I strayed once, and all that year she exiled me;

her hands have never yet dealt with me mildly. 10

A lover is holy, though, and can’t be harmed,

not if he strides by Sciron’s den unarmed;

no savages will threaten him with blows,

not if through Scythia’s wilderness he goes.

Moons show the way; stars light each jagged shelf;

Love lifts his torch and leads him on himself.

A mad dog with its slavering jaws steers clear:

the path a lover treads is free of fear.

What fiend would stain his fingers with the thinned

blood of a lover who calls Venus friend? 20

What if I knew that if I went I’d die –

but that’s a death that I would gladly buy!

She’ll wreathe my bier with roses, cast perfume

into the flames, keep vigil at my tomb.

Gods, just don’t let her bury me along

the highway where those herds of peasants throng

and scribble insults over lovers’ stones.

Far from the road, let a tree shade my bones;

or shroud me in sands, which hold no memory;

but no roadside memorial for me!

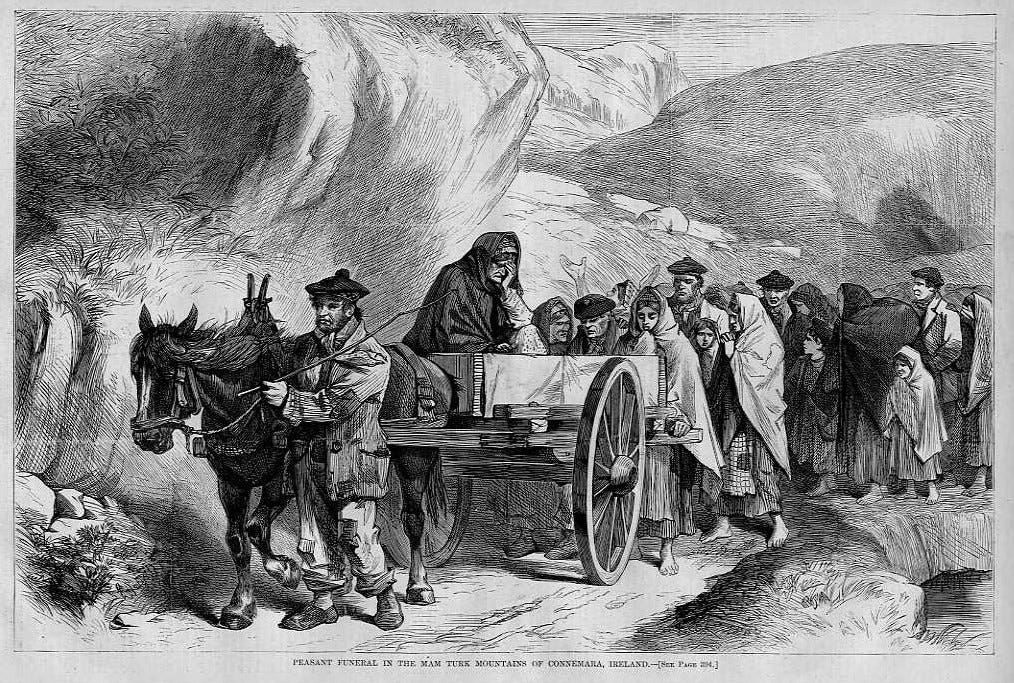

I wouldn’t want to suggest that Longley, over the course of his long life in letters, became the poet he thinks Propertius could have been had he survived to write more; still, Longley’s work is both rich and controlled and not uninfluenced by the love elegists he read so well in his youth. An excellent version of Tibullus 1.10, which Longley titles “Peace,” in commenting obliquely on the Troubles from the midst of them, operates similarly to “Cease-fire.” A sonnet called “Sulpicia” borrows motifs from her elegy / epigram. And in the following poem, “Detour,” Longley draws, quite clearly in my opinion, on Propertius’ penchant, illustrated in both poems above, for stage-managing his own obsequies. Longley also does what all true poets do, in assimilating his influences to his own context and concerns, in this case, for the homely objects and humble inhabitants of an Irish village. As for his funeral, I hope it went as he wished. Peace to him.

Detour

Michael Longley (1939 - 1/22/25)

I want my funeral to include this detour

Down the single street of a small market town,

On either side of the procession such names

As Philbin, O’Malley, MacNamara, Keane.

A reverent pause to let a herd of milkers pass

Will bring me face to face with grubby parsnips,

Cauliflowers that glitter after a sunshower,

Then hay rakes, broom handles, gas cylinders.

Reflected in the slow sequence of shop windows

I shall be part of the action when his wife

Draining the potatoes into a steamy sink

Calls to the butcher to get ready for dinner

And the publican descends to change a barrel.

From behind the one locked door for miles around

I shall prolong a detailed conversation

With the man in the concrete telephone kiosk

About where my funeral might be going next.