Dust in Love: Quevedo's "Exaltation" of Propertius

The love elegist's ashes are rekindled in one of the great sonnets of the Spanish Golden Age

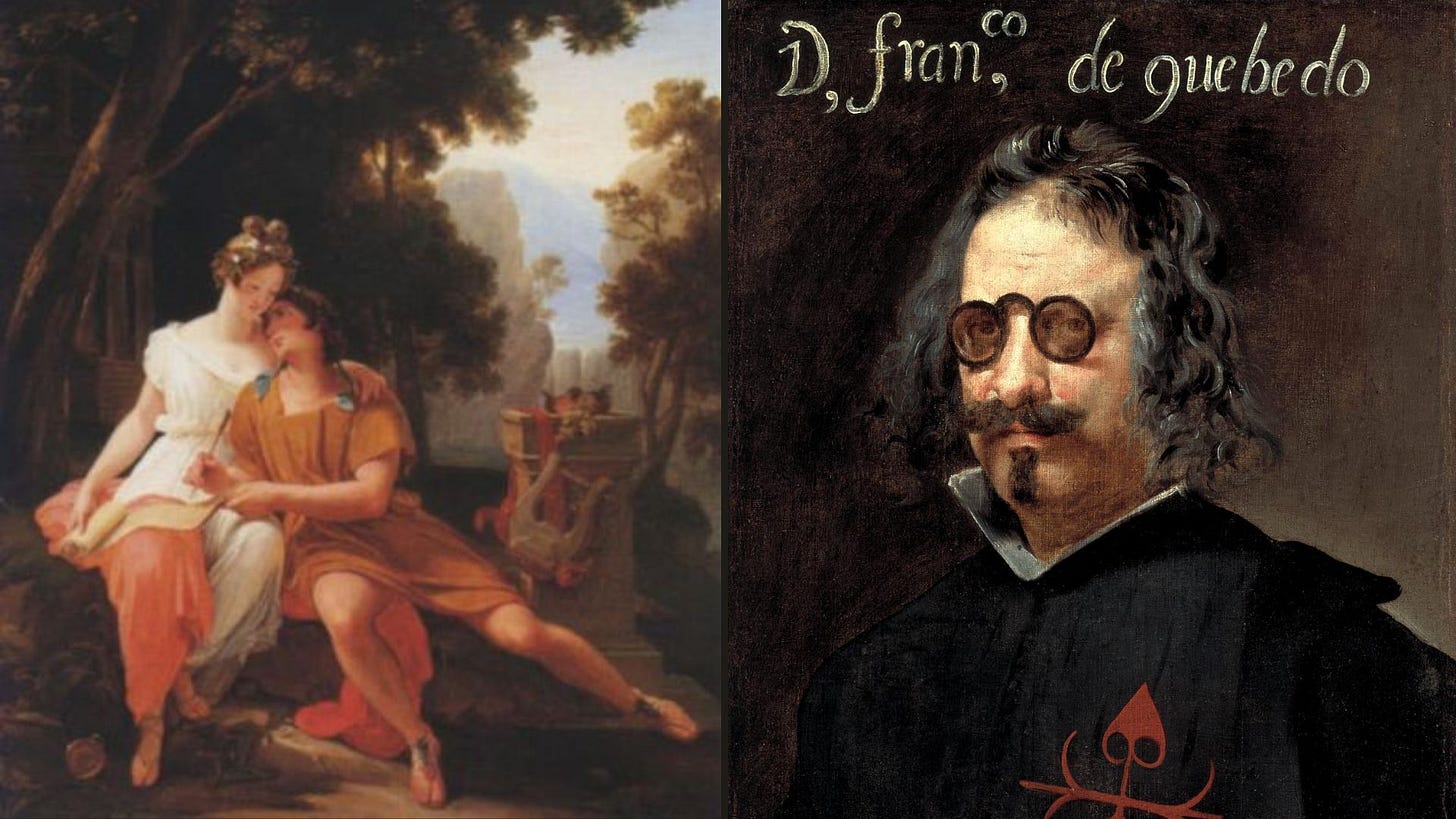

Borges writes, in an essay on Francisco de Quevedo (Other Inquistions / Otras Inquisiciones, pub. 1952): “Not infrequently, Quevedo’s point of departure is a classic text. Thus, the memorable line polvo serán, mas polvo enamorado is a recreation, or exaltation, of one of Propertius’ (Elegy I.19, l. 6): ut meus oblito pulvis amore vacet.”

You can read my translation of Propertius I.19 here, or listen to me read it if you prefer. That’s what two great friends, Dylan Carpenter and Ryan Wilson, did a couple months ago; both independently averted me to the fact that Propertius’ poem is the clear basis for Quevedo’s great sonnet, which I’d like to discuss here; not incidentally, both Dylan and Ryan have translated it. I’ll share Dylan’s translation at the top and my own attempt at the end. Dylan is a virtuoso poet and fluent Spanish speaker, thanks to the four years he spent living in Spain. I am NOT fluent in Spanish, and don’t dare to read the original aloud, but here is one of the less over-the-top performances I could find on youtube.

Amor constante, más allá de la muerte

Cerrar podrá mis ojos la postrera

sombra que me llevare el blanco día,

y podrá desatar esta alma mía

hora a su afán ansioso lisonjera;

mas no, de esotra parte, en la ribera,

dejará la memoria, en donde ardía:

nadar sabe mi llama la agua fría,

y perder el respeto a ley severa.

Alma a quien todo un dios prisión ha sido,

venas que humor a tanto fuego han dado,

medulas que han gloriosamente ardido,

su cuerpo dejará, no su cuidado;

serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido;

polvo serán, mas polvo enamorado.Constant Love Out Beyond Death

Closing my eyes the final shadow may

Grant my soul's wish to be undone from this

Enmeshment, in the hour of eagerness,

And carry me away on the white day.

But it won't leave the memory ashore

Of how it used to burn. That part of me,

My flame, knows how to swim in the cold sea

And scorn the laws I've lost all reverence for.

Soul, all but imprisoned by God above,

Veins that set every sentiment ablaze,

Bones that gloriously flare and flash—

The body vanishes, desire stays.

You will be ash one day but feeling ash.

You will be dust one day but dust in love.

Trans.: Dylan Carpenter

The first thing I hope you notice is how Dylan has nailed the last three lines—I don’t think they can land better than they do here. The first 11, however, are a mare’s nest of problems in Spanish, which he has navigated, making choices along the way, as we all must, and done a better job than most.

I don’t mean to chastise Quevedo’s translators. The poem itself is impossible, a true marvel of ambiguity, though its overall claim, that the poet’s love will endure beyond death, is perfectly clear. In its detail, though, it’s like one of those reversible figure illusions which goes back and forth between a rabbit and a duck or from your wife to your mother-in-law. It’s taken me a while to get here, but I believe that Quevedo is equivocating magnificently, speaking out of two sides of his mouth simultaneously—addressing both his pagan literary sources (Propertius and Horace) and his Christian milieu. The marvel is that Quevedo’s poem is equally at home in either context.

I invite readers of Spanish, especially those dubious that there is anything ambiguous about one of their most revered poems, to consider this detailed discussion, by Pablo Juaralde Pou, of what he calls Quevedo’s “galamatías sintáctico.” I have no intention to deal with it so exhaustively. But I want to point to three moments which I think illustrate my idea: First, what is meant by el blanco día in line 2? Second, which shore is da esotra parte in line 5? Third, in line 9, should dios (“god/God”) be capitalized? For interpretation and translation much hangs on the answers to these questions. Let me address each in turn.

1. What is meant by el blanco día, ‘the white day,’ in line 2? My contention is that, in a Roman context, it refers simply to life, while a Christian reading would connect it to the afterlife, the “white radiance of eternity” as Shelley (certainly no Christian) put it. What I call the Christian reading is less common among the translations I’ve seen, though Dylan’s version is an exception, and cannot be proved wrong by reference to the Spanish—the available meanings of llevare are wide enough and the syntax ambiguous enough that it can be construed in several ways. The phrase itself, blanco día, is strikingly mystical and certainly does not sound like it refers to ordinary daylight. But on the other side sits Horace. An alternative textual reading of Ode 4.7 (ll. 7-8) runs album quae rapit hora diem — “the hour which steals the white day.” That seems pretty relevant. While the Horace text I’m used to reads almum instead of album, viz., “the nourishing day,” it’s likely enough Quevedo read album, or knew it as a possibility. This is the interpretation most translators seem to take:

Rhina Espaillat: “When the last shadow comes to douse the white / radiance of day”

AZ Foreman: “That terminal shadow may with darkness seal / my eyes shut when it steals white day from me”

Ryan Wilson: “The final shade / Which carries the white day away from me”

Willis Barnstone: “The final shadow that will close my eyes / will in its darkness take me from white day”

2. Second, which shore is meant in line 5 — is it the near / hither shore of life, or the far shore of death? This is an interpretive question, but it is inextricable from the syntactical one: what is the subject of the verb dejará (will abandon)—alma “soul” or hora “hour” [viz., of death]? Perhaps unexpectedly, the “near shore” generates the pagan, the “far shore” the Christian reading. In either case, Quevedo asserts that what we usually assume will happen to memory in death will not apply to him; it’s just that different readers assume different things.

For the most part, the Romans will have expected departed souls to forget their lives, perhaps after a swig of Lethe. In a famous passage in Aeneid VI, Virgil has the dead souls who are destined to return to the upper world drink “long oblivion” (longa oblivia) from that river, so they don’t remember their previous life in their future one. When Propertius wrote his elegy I.19 — the poem Quevedo’s sonnet is modeled after — he would not yet have read the Aeneid ; his first book of elegies, commonly referred to as the Monobiblos, came out around 28 BC, when Virgil was only just getting started on his epic. Yet Propertius would have known Plato’s Republic, where the souls destined for resurrection gather on the Plain of Lethe to drink from the River of Carelessness (621a), as well as the Odyssey, where Circe claims that ghosts (with the notable exception of Tiresias) do not retain knowledge in the Underworld (X.493-5). Propertius also knew that he was contradicting Catullus’ bitter certainty about the silent imperviousness of the dead: mutam nequiquam alloquerer cinerem, says Catullus to his dead brother (101.4), “I shall call on your mute ash in vain”—though Propertius’ tentative conditional in ll. 19-20 (“If you, in life, could sense my ash was sad, / then death, no matter where, would not be bad”) carries little conviction that the reality of death will meet his romantic hopes.

In a Christian eternal life, by contrast, we should expect the dead to remember their lives and rejoice when reunited with their dear ones after death. If we follow Quevedo scholar James O. Crosby and take alma as the subject of dejará, we will arrive at his gloss (quoted by Pou): “My soul will not leave the memory of love on the shore of the world of the living, where she/it had burned.” In this reading, love will not be left behind, in accordance with pagan expectations, as a material residuum on earth, to dissipate in a puff of wind or be swallowed up by soil, while the poet’s gibbering ghost forgets all but the vague taste of blood; on the contrary, Quevedo asserts (with Propertius) that “great love gains even those far, fatal shores,” and that his memorious imago will return to infuse his ash with love.

De esotra parte, Fernando Lázaro Carreter thinks the subject of dejará is obviously “the hour [of death],” and understands Quevedo as meaning that “death will not leave behind, on its own far shore, the memory of love, in which the soul burned.” The body remains in the ground, while the mindful soul flies off, to await the happy celestial reunion; but Quevedo’s love is so powerful that it will impel his soul back as a revenant to the world and the ash it will fill with feeling. In both readings, then, the departing soul takes its memory of love with it into death, only to recross the cold channel separating death from life; the difference lies in the likely expectations of the (pagan or Christian) reader.

If we consider what translators have done with this crux, it is interesting once again to find them mostly on the pagan side. Foreman is most explicit, but Rhina and Barnstone are right there with him:

AZ Foreman: “But on this hither shore where once it burned / it shall not leave behind love’s memory”

Rhina Espaillat: “but soul will not abandon in its flight / memory, where it burned;”

Willis Barnstone: “and yet my soul won’t leave its memory / of love there on the shore where it has burned”

Ryan, however, takes the Christian reading:

Ryan Wilson: “But it will never leave the memory / Of where my passion burned on the far shore[.]”

Dylan, to his credit, maintains Quevedo’s ambiguity, both as to the subject of the verb, and which shore is being referred to: “but it won’t leave the memory ashore / of how it used to burn.”

3. Finally, in line 9, should ‘dios’ be capitalized? You will not be surprised that I think the choice rides on the pagan or Christian valence one wishes to emphasize. Pou remarks: “The verse Alma a quien todo un dios prisión ha sido can be understood in two different ways: either God is the prison of the soul, or the soul has served as prison to a whole god (the passion of love),” viz., Cupid, the “boy” Propertius says (in his line 5) has not “clung lightly to his eyes” (or, as my translation has it, “He’s not a joke, the boy I’m victim of”). As a reader of Latin poetry, I have no trouble imagining Cupid imprisoned in the poet’s breast, but I have a slightly harder time understanding what it might mean for the soul to be imprisoned in God—presumably that God imprisoned the poet’s soul in his body, though perhaps a religious ley severa requiring pious good behavior as regards alcohol and sex may also have felt a bit constraining to the licentious and dissipated Quevedo. In any event, the translations I know are pretty evenly split here, between Christian and pagan readings:

Christian:

Rhina: “My soul, for whom the cell god’s will has been”

Ponce: “Soul, for whom a god has been a prison”

Dylan: “Soul, all but imprisoned by God above”Pagan:

Foreman: This soul that was a god’s hot prison cell

Ryan: A soul in which a whole god has been pent

Barnstone: My soul, whom a God made his prison of

I suppose that Rhina and Ponce, who write “god” in the lowercase, feel it equally possible for Cupid to have imprisoned Quevedo as to have been imprisoned within him, and perhaps they are right, though I think Willis Barnstone’s capitalization is as confused as his line is clunky.

To wrap up, because this has gotten long: Pou, in his article, asks whether Quevedo’s galamatías sintáctico should be blamed on a period style, conscious intention, or bad writing. If I’m right that the poem reads one way in the light of its Counter-Reformation context, but another in that of its Roman antecedents, it must follow that the ambiguity is intentional. What that ambiguity might imply, however, I should leave to those who know more about Quevedo. He was clearly no irrelegionist, having denounced atheism in a theological tract, but also no saint, in that he cohabited a long time with a woman he never married, before being forced to wed someone respectable (whom he divorced after three months). He made many enemies and eventually ran afoul of the authorities and was imprisoned in a convent. A more secular reader, like myself, might prefer to believe that he crafted such a sublime equivocation because he found it unsafe to state clearly his true pagan sympathies; though it is equally possible, and perhaps more likely given his clear devoutness, to feel that the poem’s duality shows how Christian revelation completes and transcends pagan learning. Ryan Wilson will argue attractively, in a forthcoming interview, that the poem’s ambiguities are of a piece with its thematic fusion of opposites, of life with death and love with dust. Or it might be that it reads us, and that’s the point. If so, my own attempted translation, whatever its flaws, places me squarely on the side of the pagans; and of course I find it satisfying to see Propertius’ old ashes kindled to new life in Quevedo’s magnificent poem:

Well may some shadow cancel the white day for me for good and close my eyes’ discerning, when my soul, coaxed beyond its dread and yearning by liberating time, may slip away, yet will not suffer memory to stay behind it on the shore where it lay burning: my flame can breast the frigid waters churning and flout a law too heartless to obey. My soul, which a great god was prisoner of; my veins, from which my love-heat drank its fill; my marrow, glorying to be on fire, will let my body go, not my desire; will become ash, but ash with feeling still; will be made dust, but dust still quick with love.