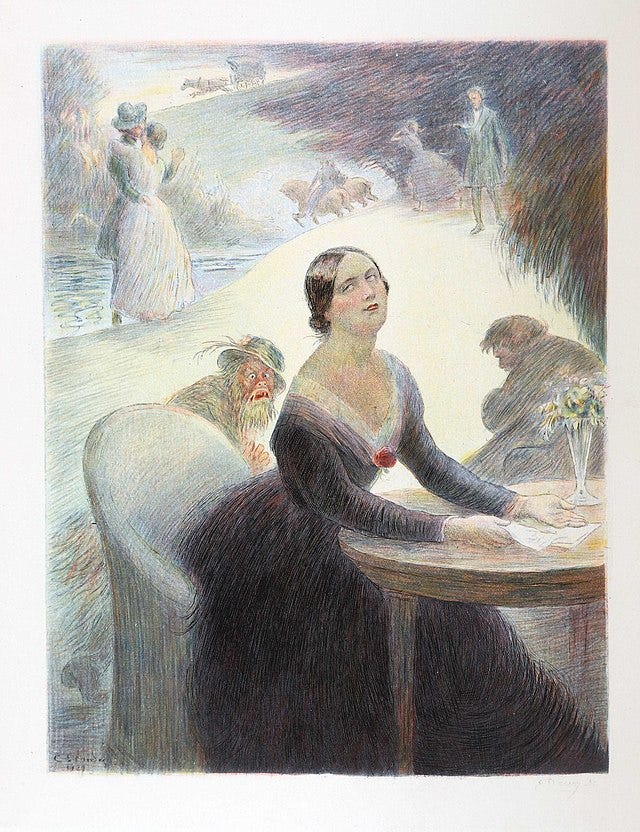

Emma Bovary, on her weekly trips to Rouen to see her lover Léon, would pass a blind beggar whom Flaubert describes as follows:

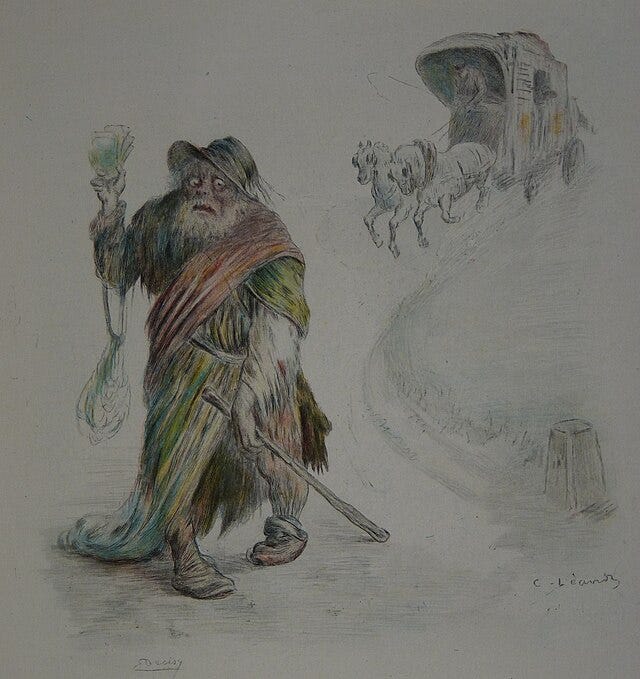

There was a wretched creature on the hillside, who would wander about with his stick right in the midst of the carriages. A mass of rags covered his shoulders, and an old staved-in beaver hat, shaped like a basin, hid his face; but when he took it off he revealed two gaping bloody orbits in the place of eyelids. The flesh hung in red strips; and from them flowed a liquid which congealed into green scales reaching down to his nose with its black nostrils, which kept sniffing convulsively. To speak to you he threw back his head with an idiotic laugh; — then his bluish eyeballs, rolling round and round, would rub against the open wound near the temples. (trans: Aveling/de Man)

His voice strikes Emma as “like an inarticulate lament of some vague despair;” it fills her with dread, “like a whirlwind in an abyss.” It is the last thing she hears. She is in the middle of her death throes when

Suddenly from the pavement outside came the loud noise of wooden shoes and the clattering of a stick; and a voice rose—a raucous voice—that sang:

Often the heat of a summer’s day

Makes a young girl dream her heart away.Emma raised herself like a galvanized corpse, her hair streaming, her eyes fixed, staring.

To gather up all the new-cut stalks

Of wheat left by the scythe’s cold swing.

Nanette bends over as she walks

Toward the furrows from where they spring.“The blind man!” she cried.

And Emma began to laugh, an atrocious, frantic, desperate laugh, thinking she saw the hideous face of the poor wretch loom out of the eternal darkness like a menace.

You’d have to be a houseplant or an undergraduate not to notice the freightedness of this figure, who has no doubt inspired reams of interpretation from the Flaubertistes—I wouldn’t know, I haven’t read them, though Vargos Llosa’s book looks worthwhile. I do recall James Wood, in How Fiction Works, remarking on “the tiresome burden of ‘chosenness’ we feel around Flaubert’s details, and the implication of that chosenness for the novelist’s characters,” a barb Wood aims at an even more minor figure who is only glimpsed once at a ball and never again. I can imagine, for a hard-working critic like James Wood, a sense of responsibility to explicate every detail may indeed feel fatiguing. Nonetheless, I find the Flaubertian “chosenness” much less tiresome than rich. There’s no doubt that, like everything else this author includes, the blind beggar is full of significance for the heroine and the novel.

My take on the character springs from having caught an adaptation of Aeschylus’ Oresteia recently while I was reading MB and, for all I know, may well be old hat. He is a polyvalent figure, but at least one of his valences seems to be that of the Aeschylean Erinnys. Compare the bloody, oozing eyes and “mass of rags” of Flaubert’s beggar to the Delphic Pythia’s description of the Erinyes / Furies at the beginning of the Eumenides:

This gang has no wings, and they’re all black,

disgusting, and their phlegmy sores spew out

a stink that blinds and repels, and their eyes drip

a sickening ooze. Their dark rags, too, aren’t fit

to wear before the statues of the gods,

or even right to bring into the house. (ll.51-6; trans.: Shapiro/Burian)

The Erinyes are figures of Justice and vengeance, pursuers primarily of oath-breakers and matricides, though Odysseus suggests that they may look after beggars as well (Od. 17.474-6): “Therefore, / if there are any gods or any furies for beggars, / Antinous may find his death before he is married.” It is easy to psychologize them as a form of guilty hallucination, and later Greeks did just that:

As you go from Megalopolis to Messene, after advancing about seven stades, there stands on the left of the highway a sanctuary of Goddesses. They call the Goddesses themselves, as well as the district around the sanctuary, Maniae (Madnesses). In my view this is a surname of the Eumenides; in fact they say that it was here that madness overtook Orestes as punishment for shedding his mother’s blood. [Pausanias, Description of Greece, 8.34.1]

So, for that matter, does Racine. Orestes sees them at the end of Andromaque, though his friend Pylades makes it clear he’s having an “episode:”

OR: I know now: daughters of Hades, are you there?

From whom these hissing serpents in your hair,

And all these presences of pain and fright?

Do you come to drag me into endless night? …PY: His senses leave him. Friends, we must not waste

The time this seizure grants us. Come, make haste

And save him. If he wakens here again

Still frenzied, all our efforts will be vain. [trans: Richard Wilbur]

At any rate I feel fairly confident that Aeschylus’ Erinyes were on Flaubert’s mind, but de-mythologized and rendered psychological. It is entirely in keeping with Flaubert’s realistic method that what were deities for Aeschylus and visions for Racine should be embodied in such a grotesque and annoying figure. One of the novel’s main themes is how small, dull and mean real life is in comparison to the great tales of art. At the end of Part II Charles and Emma go to Rouen to see an opera, Lucie de Lammermoor. While Charles watches in humorous incomprehension (“Yes, but you know,” he says, “I like to understand things.”), Emma is carried on waves of rapture and disillusionment:

[S]uch happiness, she realized, was a lie, a mockery to taunt desire. She knew now how small the passions were that art magnified. So, striving for detachment, Emma resolved to see in this reproduction of her sorrows a mere formal fiction for the entertainment of the eye, and she smiled inwardly in scornful pity when from behind the velvet curtains at the back of the stage a man appeared in a black cloak.

And yet, for all that Emma’s tragedy is one of the real world failing to live up to the romance of novels and operas, her story is as tragic as anything in opera, the origins of which go back to the Camerata’s attempts to revive Greek drama in Renaissance Florence. In Yonville Flaubert carefully sets the stage for a Greek tragedy:

The town hall, constructed “after the designs of a Paris architect,” is a sort of Greek temple that forms the corner next to the pharmacy. On the ground floor are three Ionic columns and on the first floor a gallery with arched windows, while the crowning frieze is occupied by a Gallic cock, resting one foot upon the Charter and holding in the other the scales of Justice.

Justice (Δίκη) is the chief preoccupation of the Oresteia. Dike there is always black and white and always partial. There are no mitigating factors or extenuating circumstances. Clytemnestra does not care why Agamemnon killed Iphigenia - he did, and must pay, and that is dike. Orestes, too, does not care about Clytemnestra’s reasons and it is irrelevant that she is his mother - she killed his father, and must pay. Similarly with Orestes: he killed his mother, and as far as the Erinyes are concerned that’s the whole trial: they tell Orestes, “Death freed her from her guilt, but you’re still living” (Eu. 603). Under such a retributory imperative, it’s not easy to see how the reciprocal bloodshed can ever be resolved.

The famous solution the Oresteia offers is a trial, in which Orestes is ultimately acquitted on grounds that strike us (and probably ancient audiences as well) as woefully inadequate: Orestes’ lawyer Apollo claims that his mother’s killing of his father was the worse crime because the male is the true parent while the woman is just soil; Athena, a daddy’s girl, finds this persuasive and casts the decisive vote. What matters to the play is not so much the correctness of the verdict as the creation of an impersonal process to replace personal vengeance and transfer any blood-guilt a verdict may entail from an individual agent to the State.

The play does not end with the trial. The Erinyes are not pleased with the result, which they interpret as a personal affront to them, a clear diminution of their godhead, and threaten to poison the countryside in revenge. Athena has her work cut out to convince them to become honored and benevolent local deities—Eumenides, the kindly ones:

If you hold in awe Persuasion’s glory,

the power of my tongue to soothe and enchant,

you might live here with us. … The way

is free for you to be a landholder here,

enjoying honor justly and forever.

Eventually they yield and accept a role as the chthonic Semnai Theai, “reverend goddesses,” with a shrine near the court on the Areopagus. The play ends with a procession of the freshly renamed Eumenides following Athena to their new temple precinct and dressed in the crimson robes worn by non-citizen permanent residents in the Panathenaea.

In my view, Flaubert’s blind beggar is the Erinnys of the road to Rouen, a place of perdition. Of the dread goddesses’ various spheres, the most relevant to Emma is their guardianship of oaths—specifically, her marriage oath. They pursue oath-breakers the way he haunts her, like an atavistic incarnation of Aeschylean terror dreamed up by the landscape, like the archaic conscience of the place. In his mutilated, oozing eyesockets we see a reflection of Emma’s own psychic miasma and moral blindness which she is able to blink at and ignore only with effort. In fact, the beggar, with his staved-in beaver hat and idiotic laugh, could be the twisted twin of her husband Charles, whose red velvet-and-rabbit fur hat is described in detail in the novel’s first pages; its “dumb ugliness has depths of expression, like an imbecile’s face.”

As with the Erinyes and Orestes, the beggar’s story does not end with Emma’s, and his arc ends up being both parallel to and the inverse of theirs. When he appears to terrorize Emma at her moment of death, it turns out that he has made the trek to Yonville because of a comical meeting with the ridiculous (but far from harmless) pharmacist Homais. This pharmacist is a progressive devotee of the Enlightenment. He talks like he is translating the scientific tracts of Aristotle extempore and he nearly killed the club-footed stableboy Hippolyte by convincing Charles Bovary to perform some trendy operation on him to cure his deformity. In a (for Emma excruciating) encounter with the beggar in the carriage, Homais tells him he can cure him with “an antiphlogistic [viz., anti-inflammatory] salve of his own composition.” This salve, of course, does not work, so the beggar starts denouncing the pharmacist as a fraud and quack to everyone he meets between Yonville and Rouen. Homais retaliates with a publicity campaign against him and, in the name of public health and sanitation, ultimately of Progress, sees him locked away in an asylum. Thus, his trajectory is parallel to that of the Erinyes, in that both are domesticated from itinerant pests to stable presences in the land, where they are lodged and confined; but it is also their inverse, since for them the change is honorific and represents a positive incorporation into the fabric of society, while he is conveniently disappeared and excluded from society—as if the atavistic ugliness he incarnates presents more reality, and more truth, than the delicate progressive sensibility Homais represents can bear.

That this truth exposes Homais’ own fraudulence is to the point. Emma is a tragic figure because, while she could not endure the voice of her conscience and the image of her decay, she could not fully suppress them either; Homais is an evil one because he both can do so and has no compunction about it either. In this critique of the contemptible Homais one senses something proto-Foucauldian, who sees in the medicalized asylum a charade of authority masking a more insidious (because psychologized) form of confinement:

It is thought that Tuke and Pinel opened the asylum to medical knowledge. They did not introduce science, but a personality, whose powers borrowed from science only their disguise, or at most their justification. (Madness & Civilization, 271)

Today, bourgeois progressivism has shifted sides, from Homais to Foucault, without much improvement in results.

In the Oresteia, why should goddesses of madness, revenge and blight suddenly receive the honorific title of Eumenides and be enshrined as the kindly guarantors of prosperity? Because the threat of vengeance they represent (whether real or psychological matters little) is indispensable to civic order. Their temple stands in the landscape like a public execution, serene and ominous, a reminder of what evildoers will suffer, whether from persecuting deities or their own offended spirits, “the wind of the wings of madness.” As Athena says,

I urge my people to follow and revere

neither tyranny nor anarchy,

and to hold fear close, never to cast it out

entirely from the city. For what man

who feels no fear is able to be just?

What a wonderful essay! You’ve done subtle and convincing justice (unlike Classical Greek dike) to two of my favorite works, The Oresteia and Madame Bovary, and to their creators, Aeschylus and Gustave Flaubert, each in their own ways matchless.