Glorious Exploits: Callimachus and Lennon

The invention of the mousetrap and Euripides in the quarry

On a panel in Princeton recently with a number of brilliant writer-classicists whom I admire, an audience member observed that our poems which dipped into the “myth kitty” or otherwise alluded to classical antiquity tended to do so at a modest scale, with a focus on dailiness and domesticity. One poem took Psyche’s humble part against Venus with all her “Chanel and Givenchy;” another focused on the “daughters of wing-footed horses” (to quote Simonides), claiming “But epic had no room for donkeys, though;” a third opened with Horace and ended in a dream conversation with the poet’s incontinent dead poodle. My own poem was a (somewhat lengthy) monologue from the perspective of the peasant-fishermen of Pyrrha on Lesbos, observing Aristotle as he researched the local fauna; it drew on descriptions from his History of Animals. Was there a reason, the questioner questioned, that we weren’t tackling grand subjects in a grand style?

The panelists (including me) were in general agreement that we were mostly without the aptitude and/or appetite for grandeur, which we weren’t sure how to attain without grandiosity. Classical reference in itself can read pretty grandly, and we all felt the need for a bit of modest counterpoint, whether in diction, subject matter, or approach—we wanted to welcome readers, not intimidate them. Learning lightly worn, erudition relaxing at the pub, ambition posting cat photos — that’s how we felt comfortable using the Classics, whether as a matter of tone, or an embrace of our full selves: yes, Sophocles is sublime, but cats are also cute. Maybe we’re just Americans with an ingrained suspicion of snobbery. A poem like “Ceasefire,” much discussed lately for sad reasons, tackles a literally epic subject, but in a modest approachable style typical of Michael Longley’s Homer poems, where the syntax can be virtuosic but the diction is in a lower register, and often very Irish. Anthony Hecht’s sonnet “The Witch of Endor” gives an example of what we were all trying not to do: take a highbrow (in this case Biblical) subject, and deck it in equally florid diction: the Shakespearean “vasty deep,” “tumid flesh,” “sortilege,” “thaumaturges,” with an ending on Samuel’s “hollow, deep, engastrimythic voice.” If all that is in your home register, the poem is fine, albeit slight; if not — and for most readers it won’t be — the game isn’t worth the candle.

At the time I wished Elijah Perseus Blumov had been present at our panel, because he would have disagreed with, and probably out-argued us. For him (at least as I understand him), life is too short, and too fraught with light charm, gentle humor, and banal domesticity, for our art to be, too. He wants a poetry that does not succeed merely because it does not aspire, but which tackles the deepest and highest themes, in a diction commensurate with the seriousness of the subject. Elijah, like his Old Testament namesake, might have thundered that we, the assembled bobbleheads, lacked the skill, or ambition, or nerve to clasp the lightning with both hands, and (in my case anyway) he might well have been (might be) right. Ultimately the proof will be in the work—can an unapologetically grand, all-out ‘metal’ modern ancient tragedy actually gain acceptance and work powerfully on its audience?

I have my doubts, and my sensibility, which is more Hellenistic than Hellenic. I said as much in my response to the question: that the fixation on dailiness and the search for human-sized forms and approaches to grand mythical dramas are characteristic of both Hellenistic Greek verse and our own era. After the death of Alexander, the idea of a Panhellenic identity, always fragile if not illusory, fragmented again, when the expanded Greek world suddenly became a battleground of competing generals, and the old center of gravity moved to the margins, from mainland Greece to Macedon, Anatolia, and Egypt. At Alexandria in particular, scholars worked to collect, preserve and reinterpret the masterpieces of Archaic and Classical antiquity, but focused much of their own poetic energies on lower, ‘unpoetic’ topics: housewives confabulating, dedications at wayside shrines, elegies for pets. Characteristic genres shifted from drama, epic, and elegy to mime, epyllion and epigram.

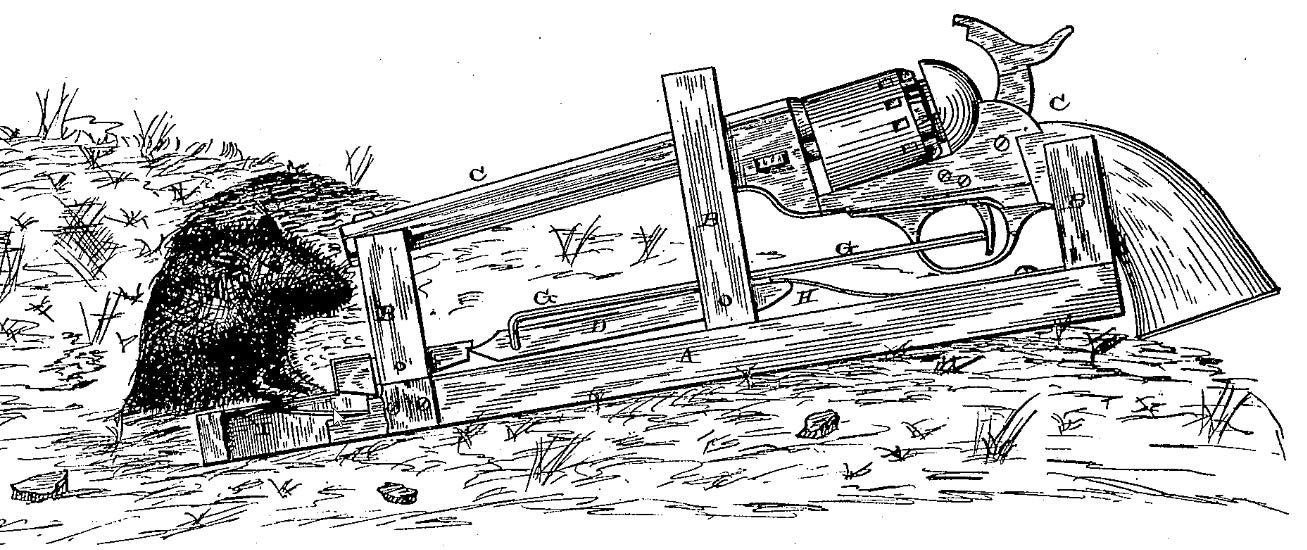

Callimachus, a poet-librarian who served mostly under Ptolemy II Philadelphus, provides several early and fully fleshed examples of this fashion, of which he was trailblazer and trendsetter. In his epyllion (mini-epic) Hecale, he narrates Theseus’ heroic labor killing the Bull of Marathon with a focus on a kindly old woman, Hecale, who gives him shelter on his way to his glorious exploit. Similarly, in the Victory of Berenice, Callimachus praises the Ptolemaic queen’s chariot victory at Nemea by telling of the peasant Molorchus, who hosted Heracles on his way to kill the Nemean lion before founding the Nemean games. Molorchus spends much of the poem complaining to Heracles about a rodent infestation and has the distinction (thanks to Callimachus’s poem) of being the mythical inventor of the mousetrap. The poem is fragmentary, but here is a surviving section focused on Molorchus and his mice:

ἀστὴρ δ' εὖτ'] ἄρ' ἔμελλε βοῶν ἄπο μέσσαβα [λύσειν

[ αὔλιος], ὃς δυθμὴν εἶσιν ὕπ' ἠελίου

[ ]ὡς κεῖνος Ὀφιονίδῃσι φαείν[ει

[ ]θεῶν τοῖσι παλαιοτέροις,

[ ]τηρι θύρην· ὁ δ' ὅτ' ἔκλυεν ἠχ[ήν,

[ ὡς ὁπότ' ὀκν]ηρῆς ἴαχ' ἐπ' οὖς ἐλάφου 10

σκ]ύμνος, [μέ]λλ[ε] μὲν ὅσσον ἀκουέμεν, ἦκα δ' ἔλ[εξεν·

"ὀχληροί, τί τό[δ'] αὖ γείτονες ἡμέ[τ]ερον

ἥκατ' ἀποκναίσοντες, ἐπεὶ μάλα [γ'] οὔτι φέρο[ισθε;

ξ]είνοις κωκυμοὺς ἔπλασεν ὔμμε θεός.’

ὣ]ς ἐνέπων τὸ μὲν ἔργον, ὅ οἱ μετὰ [. . .].ινε[ 15

ῥῖ]ψεν, [ἐ]πεὶ σμίνθοις κ[ρ]υπτὸν ἔτευχε δόλον·

ἐν δ' ἐτίθει παγίδεσσιν ὀλέθρια δείλατα δοιαῖς

αἴ]ρινο[ν ἐ]λλεβ[όρῳ] μίγδα μάλευρον ἑλών

. .]ντ.[.]ωιτα.α[. . . . . . . .]. . θάνατον δὲ κάλ[υψε

. .].κ.[.].[. . .]γειη.[. . . .].αγ̣ωσιν ἔπι 20

. .]ημ.ν[. ὡ]ς κίρκο[ι. . . .]. . .ἄρτι πεσόν[τες

πολλάκις ἐκ λύχνου πῖον ἔλειξαν ἔαρ

ἀλκαίαις ἀφύσαντες, ὅτ' οὐκ ἐπὶ πῶμα[τ' ἔκειτο

ἅλ]μαις καὶ φιάλῃς, ἢ̣ ὁπότ' ἐξ ἑτέρης

εἴλησαν χηλοῖο, τά τ' ἀνέρος ἔργα πενιχροῦ 25

. . .]ο.οκ. . .σκληροῦ σκίμπ[τετο λ]ᾶος ὕπο

κλ]ισμὸν α. . .τεπ[. . . . . . . ω]ρχήσα[ντο

βρέγματι, καὶ κανθῶν ἤλασαν ὦρον ἄπο,

ἀλλὰ τόδ' οἱ σίνται βρα[χέ]ῃ ἔνι νυκτὶ τέλεσσαν,

κύντατον, ᾧ πλεῖστ[ον] μήνατο κεῖνος ἔπι, 30

ἄμφ[ιά] οἱ σισύρην [τ]ε κακοὶ κίβισίν τε διέβρον·

τοῖς]ι [δὲ] διχθαδίους εὐτύκασεν φονέας,

ἶπόν τ' ἀνδίκτην τε μάλ' εἰδότα μακρὸν ἁλέσθαι.

].[.]. .ἀνέλυσε θύρηνAt sunset, when the evening star grew bright

to ease the oxen’s necks and light the night,

while deep down where the old gods are, the sun

was shining for the sons of Ophion,

a knife-scrape scratched the door. He quailed with fear,

as if a lion cub roared at a deer,

then paused, and craned to hear, and softly said,

“You pests, bad neighbors, why show up to shred

and gnaw my house? They’ll cost you though, these feasts—

you bane for guests, you grief from god, you beasts!” 20

He let what he was doing drop right there,

unfinished, and he started on a snare—

two mouse-traps, rigged with fatal bait, comprised

of flour and hellebore and death disguised. …The mice would use their lions’ tails to scoop

the lamp-oil, swooping on it as hawks swoop,

and lap the sweet fat up, and when the lid

was off the pickle jars, or when they slid

open some other chest, and nibbled on

the work of his poor hands with the stone gone, 30

then, as he tossed unsleeping on the bed,

the whole night they would tap-dance on his head.But this, this galled him most: those ravening

creatures, in one night—oh shameless thing!—

devoured his clothes, his blanket, and his pack.

Now he wrought double death to get them back:

a trap with crushing bar and leaping spring,

and cracked the door…

I thought of this passage recently when reading Glorious Exploits, the debut novel from Irish writer Ferdia Lennon, which appeared in March of last year, and which to me shares the sort of Hellenistic sensibility I’ve been describing: the book is haunted by Euripides, as are (I would suggest) the Hellenistic era and our own, much more so than by Sophocles. It is set in Syracuse during the Peloponnesian Wars, in the wake of Athens’ failed invasion of Sicily. The Syracusans, embittered by Athenian atrocities, have decided to use their limestone quarries as a cruel prison for their captives. The book’s protagonists are two unemployed potters, Gelon, a fanatic of Euripides, and Lampo, the point-of-view character, who (not unlike many of Longley’s Homeric poems) narrates the action in a demotic Irish brogue. Though it takes some getting used to, the choice is a good one for several reasons: first, because it conveys the class status of the narrator and his friend, as measured against the ‘aristos’ with whom they have several run-ins; second, as a kind of analogue for what would surely have been a twangily provincial brand of Syracusan Doric; and third, because it comes easily and naturally to the author. We’ve had enough sword-and-sandals epic that speak the Queen’s English. As Lampo would say, “Grand so.”

The plot revolves around a double-header production of Euripides’ Medea and Trojan Women which the two down-at-heels protagonists decide to direct in the quarry, with the emaciated Athenian POWs as the cast. Glorious Exploits is marketed as a comedy, and I picked it up expecting to laugh; but, while there are a few moderately amusing moments—the one springs to mind where Lampo suddenly comes into some money and immediately squanders it on a bright blue chiton and crocodile boots—the overall impression I’m left with is one of brutality, mostly in the way the Syracusans treat their prisoners, but also in the Athenians’ early prosecution of the war, especially their incineration of the town of Hyccara. The book is not quite as sadistic as Flaubert’s Salammbo, but it’s in the neighborhood.

Lennon is a fine writer and his tale is well put-together, though there are times when one feels the novelistic gears grinding a bit. Lampo’s early run-in with ‘aristos’ appears to set up a class-conflict that never really comes to fruition. There is a rich ex-slave called Tuireann (after a tragic character of Irish myth) from the ‘tin islands’ who appears as a sort of stand-in for the author and functions as the deux ex machina who makes the plot work. Some of the other surrounding characters, too, don’t feel too fully imagined, beyond the needs of the story. Nevertheless, I found the climax quite satisfying, Lampo’s character evolves in a meaningfully sympathetic way, and the writing can be powerful. I particularly liked the (iambic pentameter) sentence, describing conditions in the quarry, “A fist of sun emits a bruising light,” and did enjoy the demotic Irishness of “Cassandra is a regular wreck the buzz.” My favorite bit, though, was probably this passage, which comes near the climax, and glosses both the main characters’ objective in staging their play, and the novelist’s in writing the book. It should be noted that Helios is Gelon’s little son who died before the start of the novel, and the quarry is menacingly, disgustingly ridden with rats. Lampo is blowing the aulos to try to catch the attention of Athenians behind the quarry fence:

I take a drowning man’s gulp of air and blow into the fucker with everything I’ve got. The aulos rings out across the quarry, properly loud now, louder than any real bird, but with the wind and the rain, it might pass. I play, though of course you couldn’t really call what I’m doing playing, but it clashes with the scurrying of rats, their awful screeching, and in my mind, those rats aren’t just rats, they’re everything in the world that’s broken. They’re things falling apart, and the part of you that wants them to. They’re the Athenians burning Hyccara and the Syracusans chucking those Athenians into the quarry. They’re the invisible disease that ate away at the insides of little Helios till he couldn’t walk or, in the end, even speak, just cry with pain. Those rats are the worst of everything under an indifferent sky, but the sound coming from the aulos, frail as it might be in comparison, well, that’s us, I say to myself, that’s us giving it a go, it’s us building shit, and singing songs, and cooking food, it’s kisses, and stories told over a winter fire, it’s decency, and all we’ll ever have to give, I say to myself, as my lungs burn and my eyes water, ‘cause I don’t have much left, but I keep blowing away at the aulos, playing my song, but the rats are as loud as ever, and this is madness, I’m pouring water in the desert, hoping flowers grow, what does it even matter if a few do, we’re fucked, and the music stops.

Henry James said, “We work in the dark. We do what we can. We give what we have.” In this passage I admire Ferdia Lennon “giving it a go,” in a wildly demanding form—I forget who said that making historical fiction is like writing a PhD thesis at the same time as you produce a novel. The payoff comes in the way tales like this one use character and story to open previously inaccessible regions of the past to imagination. The book is not immune to quibbles—here, for instance, I could wish that the symbolism of the rats was not stated quite so baldly—but few books are, and this one accomplishes much that commands respect. If the scale is self-consciously - one might say Hellenistically - small, well, that’s the scale at which most everyone I know lives and writes. The title, Glorious Exploits, is seriously ironic, in that it asks, in the manner of Falstaff or Euripides, what glory is and means. And I will remember for a long time the depiction, at the end of the book, of Euripides, on the eve of leaving Athens for the court of the Macedonian king Archelaus, as a man who “was ever in love with misfortune and believed the world a wounded thing that can only be healed by story.”