“You’re not from around here are you?” is the question I fielded most often during the year or so I spent waiting tables. I had taken the job because a waiter’s schedule seemed compatible with continuing to translate the mega biblion I was already entering my second decade of working on. So I pitched my tent in one or another coffee shop each morning until around 4 or so, when I would snap on the white double-breasted chef’s jacket they made us wear and leg it down to the restaurant, located in a historic former bank with a beautiful Tiffany glass dome about a block away from Strip Club Row.

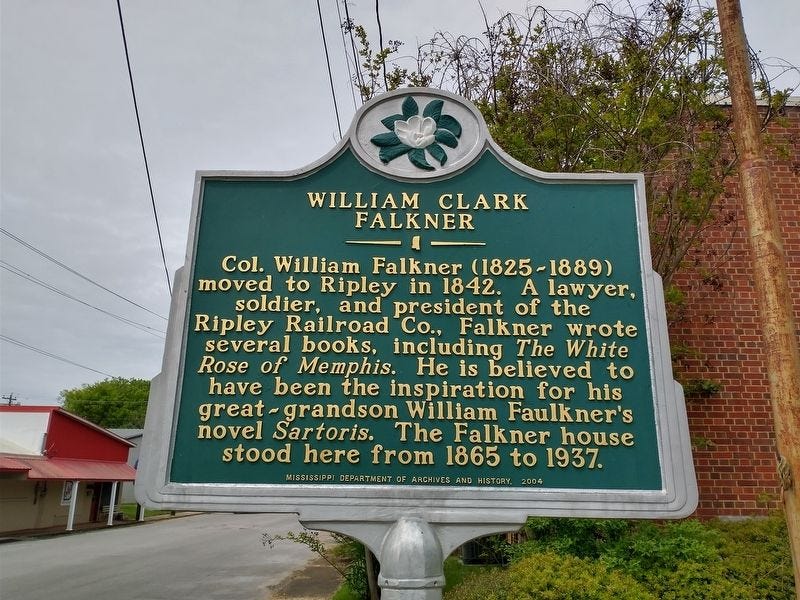

It was certainly true that I wasn’t from around there, there being downtown Baltimore. I’m a southerner by birth, born and raised in Memphis, TN, with old Mississippi heritage on my father’s side ultimately going back to Jamestown, while my mother is the product of third or fourth generation German immigrants who settled near Cincinnati. An interesting sidenote from my father’s family has his mother’s great granduncle, Dick Thurmond, shooting and killing William Faulkner’s great-grandfather on the courthouse steps in Ripley, Mississippi, apparently in a dispute over the railroad business. Accordingly I see myself as a descendant of Snopeses (NOT Compsons or Sartorises).

No doubt my waiter’s voice carried certain mannerisms which a trained ear could use to pin down if not pen down my origin — chiefly, my difficulty in hearing and articulating the distinction between a short i and short e followed by a nasal: pin & pen, tin & ten, din & den, &c.—I make them all rhyme with “in” unless I’m paying attention. Add to that that I tend to talk through my nose, often quite a bit louder than I should, a habit both my brother and I inherited from our father. Nonetheless, at some point I lost the overt twang of the men in my family—I say my short vowels crisply, without bending them (pin, not paean / pee in). On the other hand, I have a habit of lingering over long vowels in a slightly affected way which probably developed over the hundreds if not thousands of solitary hours I spent memorizing and intoning poetry in my college dorm room and beyond.

In high school and maybe afterwards, youthful self-consciousness left me ashamed of the drawl I associated, as venomously as any Yankee, with inbreeding and yokeldom, though I’ve forgotten whether I consciously set out to scrub myself of it, or whether the study of languages, especially dead ones, and (as mentioned above) poetry did the trick instead—a trick which, I hasten to add, only got partly done, since about half the people I meet who betray any interest in my provenance immediately peg me for a southerner, while the other half are surprised. The most memorable instances are when people get it very wrong — the Americans in Italy (from Alabama and Colorado) who took me for a speaker of Strine; or, at the restaurant, the Irishman who guessed I was a Scot (or was it a Scot who guessed I was an Irishman?) and the Italian convinced I had immigrated from Germany at the age of seven.

Were the diners I puzzled confused by my voice or my words? Another way of asking this is: if there existed a transcript of whatever I said, would it be clear from the text what had confounded them, or would you need to hear a recording? On the one hand, instead of the expected Bawlmer drawl, I spoke with a distinct, muted southernness they couldn’t quite place. On the other, my academic interests had no doubt shaped my diction and syntax in ways they would have found perfectly ordinary in a classroom but which surprised them from a purveyor of crispy brussels sprouts and duck ravioli. The poor patrons did not know what they were dealing with. They just wanted their wagyu beef, which, alas, I took my sweet time in delivering.

In This is the Voice, a genial 2021 book by New Yorker writer John Colapinto, the author begins by describing a vocal injury he got from belting too hard, without proper warmup, as the frontman of a rock band at a party. The polyp reduced his voice to an uncomfortable muted rasp, with diminished emotional range and expressiveness, and transformed an obviously verbal guy into a stunted simian. Unsurprisingly, no trace of that rasp comes through in his writing, which is lucid and breezy, if not distinctive. Though he appears as a character here and there in his narrative, he is clearly the sort of writer who has taken Strunk & White to heart, and cultivated an unpretentious and engaging clarity, purged of personal quirks. It’s a book where the writing, by design, disappears.

Contrast this with a story told by the poet Jonathan Farmer in an episode of the podcast Sleerickets a couple months back. Farmer said that, when he first started reading Mary Oliver’s poems, he heard a quite specific voice in his head; and that, when he finally went to listen to her read in person, her speaking voice turned out to be exactly as his inner ear had imagined it. That’s quite a trick, if Mary Oliver has indeed pulled it off. It would be as if I, by choosing one set of words over another, could make you hear my oafish nasal bleats subtly undergirt by the Jack Daniels twang; or if Colapinto could communicate that Waitsian rasp while preserving his informative lucidity.

Tony Hoagland, in a little primer on The Art of Voice, talks about “voice poems” as one-sided conversations with an entertaining interlocutor you love to listen to. I get the feeling that, in a certain kind of poem, he likes to use the words to imagine a fully fleshed speaker, with whom he has a better than average chat:

We want to feel that we are encountering a speaker “in person,” a speaker who presents a convincingly complex version of the world and of human nature. When we commence reading a poem, we are starting a relationship, and we want that relationship to be with an interesting, resourceful companion.

This is not exactly what I want. Over and over, Hoagland quotes from the beginning of poems, many of which were quite “voice-y” and demotic. Without the rest of the poem to back them up, I loathed the voice in Mark Halliday’s “Population” or Marie Howe’s “Reading Ovid;” but after I looked them up and read each of them, I could see how the voice serves to characterize the speaker, and that it’s the relationship of the speaker to the subject matter that actually interests us, not the speaker’s voice per se. Both poems may be “voice poems” in Hoagland’s sense, but in neither of them does one feel that the poet is writing in his or own “voice.” They’re persona poems, dramatic monologues; the voice is a choice.

In his essay on “Discourse in the Novel,” Mikhail Bakhtin has a lot to say about a phenomenon he calls heteroglossia. While I found most of his specific statements basically unintelligible, a hazy general idea nonetheless emerged, which is that the study of style in a novel should not merely focus on the way the narrator builds sentences, but on all the voices the book contains, and how they relate to and interact with each other. No doubt I am missing quite a bit here, as Bakhtin takes a great number of highly abstract words to say this thing which I am making sound perfectly simple, if not simple-minded. I bring it up for the word “heteroglossia,” which I want to come back to later.

I’m approaching the heart of my discomfort with the idea of “voice.” Those, like me, who first dipped our toe into the Creative Industrial College Writing Complex in the early oughts could not escape the idea that a voice is something we all have, if only we could find it. I’ve always been skeptical. Sure, plenty of major writers do have a distinctive, recognizable “voice,” but is it actually a voice or a manner, especially if the writer is capable of sounding like lots of people besides himself? Faulkner’s distinctive prose style doesn’t stop him from ventriloquizing a wide range of speakers—he did write both As I Lay Dying and Light in August. It’s been ten years since I read either, but for whatever it’s worth I liked the first much better than the second: the first book does Yoknapatawpha in a dazzling array of voices, while in the latter Faulkner mostly just imitates himself.

I feel like my skepticism may be more widely shared today than it was in 2003. Still, I should note that some honest-to-god greats, like Seamus Heaney, do indeed speak earnestly of “finding their voice.” Heaney connects the distinctive sound of his poetry — which I associate primarily with short, grunting consonant-encrusted monosyllables — to his own speaking voice and the Ulster accent he grew up around as a child, which, he says memorably, “strikes the tangent of the consonant rather more than it rolls the circle of the vowel.” Anything that helped him produce his poems is to the good. But for me, at least, when I turn to him, I don’t do so to hear “that Heaney sound,” I do it to read good poems. (I’ve also never been able to forget someone, maybe Phil Hoy, referring to him as “the dean of the ‘Mud and Grunk’ school of poetry.”)

Considered from a certain angle, “finding your voice” is something of a koan. Here’s Colapinto:

The voice is, conceptually, impossible to “locate.” It is “in” the speaker’s body as an act of breathing and articulation, but doesn’t exist until it is manifest in the air as a sound wave. Arguably, the voice comes into existence, as voice, only when someone is around to process that sound wave in the brain’s auditory cortex. (In voice science, the answer to the philosophical riddle: “Does a tree that falls in a forest make a sound if there’s no one to hear it?” is “No!”)

He goes on to list the various parts of the body involved in the production of speech — lungs, vocal chords, tongue, lips, soft palate, velum — each of which originally evolved for some other purpose. If there is no place or space in which the voice, when spoken, actually resides, how can we locate it when it isn’t even there—when words are sitting on a page rather than winging through the air?

It seems to me that the problem of “locating” the voice, of pinning it or penning it down, is another version of the problem of locating consciousness, or the self. The voice is, quite literally, an emergent property; we summon it by coordinating the efforts of most of what surrounds and surmounts the belly button, and send it forth to fly and fade. Like many life energies, voice is a verb disguised as static by the noun that names it. Similarly, consciousness is not located in the firing of any single neuron but in the concatenation of all of them in concert, just as identity is concatenated out of things like DNA, memories, habits, and desires, and who we are changes from one moment to the next, depending on whom we’re with and what we’re doing. Our selves aren’t inside us any more than our voice; they float somewhere between the mirrored glass of reaction we all hold up to each other in every encounter. All three—voice, consciousness, self—are like pointillist paintings: they hang together well enough when viewed casually from ten feet away; but peered at intently, at nose-length, they dissolve.

I wonder if, like an electron circling an atom, the voice isn’t subject to its own Uncertainty Principle—that, as a writer weighs and measures it in awareness, it suffers distortion, becomes more or less itself. I mean that locating what you consider your voice and flexing it strengthens certain muscles at the expense of others. For example, had Heaney not pinpointed his own personal essence in phrases like “snug as a gun” and “the curt cuts of an edge” at the start of his career, would he have hit upon this translation of Vergil at the end of it?

But the Sibyl,

Seeing snake-hackles bristle on his necks,

Flings him a dumpling of soporific honey

And heavily drugged grain. The ravenous triple maw

Yawns open, snaffles the sop…

I like this a lot, both as a rendering of the passage and a Heaneyesque performance of himself, and I’m glad it exists, but (as I’ve discussed elsewhere) it’s not particularly Vergilian.

No doubt this is the longest yet I’ve gone on this blog before mentioning translation. Ultimately, you’ll be relieved to learn, that is my destination. As the non-multitudinous author of a rather hefty tome, consisting of 80+ quite different poets who lived and wrote over the course of some eight centuries, it is fair to ask how a single individual with a single instrument could give voice to such diversity. It was always one of the things I worried about: how could I make poets as different as Archilochus, Anacreon, Pindar, Philodemus and Catullus sound like themselves and not like me? My answer is that, in translation at least, voice is a problem and product of technique. I didn’t realize it at the time, but Bakhtin’s notion of heteroglossia may fit well with what my book is trying to do: playing not only voices but various formal and stylistic choices off against each other to create (hopefully) that feeling of a profusion of poets talking to and at and over each other: ex uno plura. I’ll say more about this in a subsequent post.

For now, though, I’ll close with reiterating my basic idea, which is that gallivanting off to the Dagoba System in search of one’s own voice is the wrong approach; even worse is scanning the pre-existing stylistic constellations for a patch of empty sky where you can insert a schtick nobody has hit on yet. If voice is real, it will emerge on its own, whether we want it to or not; if it’s an illusion, or a mannerism, we’ll only delude and limit ourselves by picking one and sticking with it. I think less about “finding” my own voice than not offending it—not writing anything I couldn’t actually bring myself to say. It’s more about exclusion than inclusion.

Perhaps we can divide poets into two broad camps: those, like Seamus Heaney, who work hard to sound like themselves, and those like Robert Frost, for whom "the object in writing poetry is to make all poems sound as different as possible from each other.” In the latter case most readers will still hear a consistent voice across the poems and books, even to the writer’s consternation. I suspect this has less to do with the writer than the reader, standing at precisely the right distance from the pointillist painting where it all comes together: knowing as we do that we are being addressed by a single person over however many hundreds of pages, we use them all to construct our notion of the speaker, and then hear her voice in each.

Sounds like you, Edgar Allen Poe and I all had unpleasant times in Baltimore, in my case toiling at a bank on South Charles. Hopefully, Poe had the worst of it.

BTW from your description of your accent, you sound like a Kiwi, so Strine wasn’t such a bad guess.