I had been planning to write about sapphics—in fact, was in the middle of writing about them (yes, I move slowly)—when Victoria Moul’s post on the same subject popped into my inbox last week. She, with the help of Nimrod Journal, introduced me (and no doubt at least some of you) to a fine poem by Tyson Hausdoerffer in true English sapphics, that is, a version of the quantitative Greco-Roman form adapted to our qualitative (stress-based) metrics.

Since Victoria in her piece expounded the “rules” for Greek & Roman-style Sapphics in English, I’ll direct anyone with questions to her, and delete, with relief, the swampy expository paragraphs I had been slogging through, which included this specimen of metrical doggerel, exempli gratia:

Don’t be scared of playing with English Sapphics;

it is not too difficult keeping rhythm,

though to write good poetry’s always hard, no

matter the language.

As Victoria observes, line 1 with its second-foot trochee (scared of) is more Greek in style, while lines 2 and 3, with heavier fourth syllables (not too difficult, write good poetry), are more Roman / Horatian. I might add that there is some question about the Greek sapphic whether its earliest practitioners regarded it as a quatrain with a short fourth line or a tercet with a long third line; at any rate, a harsher enjambment (as above) between lines 3 and 4 is in the spirit of Sappho’s handling.

There’s no way of knowing if Sappho “invented” her eponymous stanza or merely used it so often and well that her name stuck to it. Her contemporary Alcaeus also wrote poems in Sapphics, without (as far as one can tell from what survives) any specific reference to her. I suspect that the stanza preceded both of them, whether as a popular tune in the air or a bit of religious liturgy; my pet theory is that both poets mostly (if not exclusively) used it for hymns and prayers, in something like the way Isaac Watts buffed the folk ballad into the common measure of the Anglican hymnal.

In general, I am bearish on Greco-Roman meters in English; some of them (the ones with runs of three or more long or short syllables) are flatly impossible, while others (those with, say, strings of two or more consecutive choriambs) require a syllabic gymnastics at odds with the genius of the language; and even doable examples, like the alcaic and elegiac couplet, will still confound more readers than not. The Sapphic, however, is an exception. It has a robust tradition in English (check out THIS vintage Eratosphere thread from Joseph Bottum of Poems Ancient & Modern) and is technically feasible—yes, it takes some sweat to make each line start on a beat or to avoid weak line-endings, but with patience it can be pulled off naturally enough (witness Hausdoerffer’s poem). Here is another of my favorite examples, “Locker Room Etiquette” by the late Craig Arnold, first brought to my attention by AE Stallings, on THIS similarly vintage Eratosphere thread (scroll down a little).

I mention AES because my real goal here is not to talk about “strict” Sapphics (like Hausdoerffer’s poem) but “adapted” Sapphics, like Stallings’ wonderful recent poem in the LRB, “Anosmia,” which inspired this post. This ‘adapted Sapphic' goes 5-5-5-2 and often rhymes. It’s the form I used to translate Sapphics in the book — see this post for examples. Trochaic openings, mid-line dactyls and feminine endings are welcome but not required. Here is Stallings’ poem, which describes Covid-related smell-loss (Anosmia, a good Greek medical term):

Anosmia

by AE StallingsWithout it, what is lemon, what is mint? –

Coffee and chocolate, caffeinated brown.

Ghosted by a sense that takes no hint,

I feel let down.It’s hardly tragedy that I can’t tell

The milk’s gone off, eggs rotten. It’s no joke

With other things though – no internal bell

That signals smoke(The toast burned or the house on fire). Sweet

I have, and bitter, I have sour and salt,

But without smell, no flavour is complete.

There’s no … gestalt.It’s something I’d predict of old, old age,

This weaning from the welter of the world

The better, perhaps, to leave it. I’m no sage,

I’d rather the impearledJasmine flowers – fragrance of the stars –

Light up the brain’s grey matter, and the hurt

Of memory, the human musk of ours

In an unwashed shirt.‘To have a nose for’– isn’t it a skill,

A wry intelligence, a kind of knack?

What thought trails do I lose, untraceable,

What wisdom lack?I miss the laundry scent they call ‘unscented’.

Like a depression, it makes it hard to write.

What is is less, less there, half uninvented,

And I, not quite.But there are days I almost have a whiff:

I slice a lemon open for the crisp

Sun-saturated redolence, and sniff

And stand in the eclipse.

With every slightly off-kilter stanza choice, one should ask why this poem is in this form. Hausdoerffer tells us why he chose Sapphics when he mentions her by name in stanza 3, in relation to the Greek adjective poikilos — though he also sneaks in an implicit allusion, with the “apples gleaming out of reach in the autumn sun” in the last stanza, which nods to her fragment 105a:

An apple on a bough hangs redly, sweetly,

high on the highest limb, against the sky.

The pickers leave it be, but don’t completely

leave it – they reached for it; it was too high.

Stallings also alludes implicitly to Sappho in her third stanza — “Sweet / I have, and bitter,” which picks up the Lesbian’s famous coinage glukupikron, “bittersweet” or “sweetbitter.” Yet the real reason for the form is the sense of something missing which the foreshortened fourth line imparts. That something is of course smell, the penumbra of taste, its indescribable “gestalt,” to which the poem is an encomium in absentia. We are clued in to this form-content connection in the very first stanza, where the fourth line both establishes the pattern of “let down” and connects it to the specific anosmic “let down” it adumbrates.

Stallings’ poem wistfully evokes the lost sense by naming a number of instantly recognizable scents, whiffs of what Duns Scotus called ‘thisness’ (haecceitas)—lemon and mint, “impearled // jasmine flowers,” “the human musk of ours in a dirty shirt,” “the laundry scent they call ‘unscented.’” “Sage” in stanza 4 is not entirely scentless, though it is used scentlessly. (“Thyme/time” is another fragrant pun which might be wafting undetectably in the poem’s atmosphere.) The loss of smell forebodes the loss of self; the poet has already begun to disappear. “This weaning from the welter of the world” is a gorgeous and heart-breaking line which casts our mortal departure as a gradual, maternal sort of process; it puts me in mind of Thomas Grey’s great stanza, after which Richard Wilbur titled a similarly touching valediction of his own:

But who, to dumb forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing anxious being e’er resigned,

Left the bright precincts of the joyful day,

Nor cast one longing, ling’ring look behind?

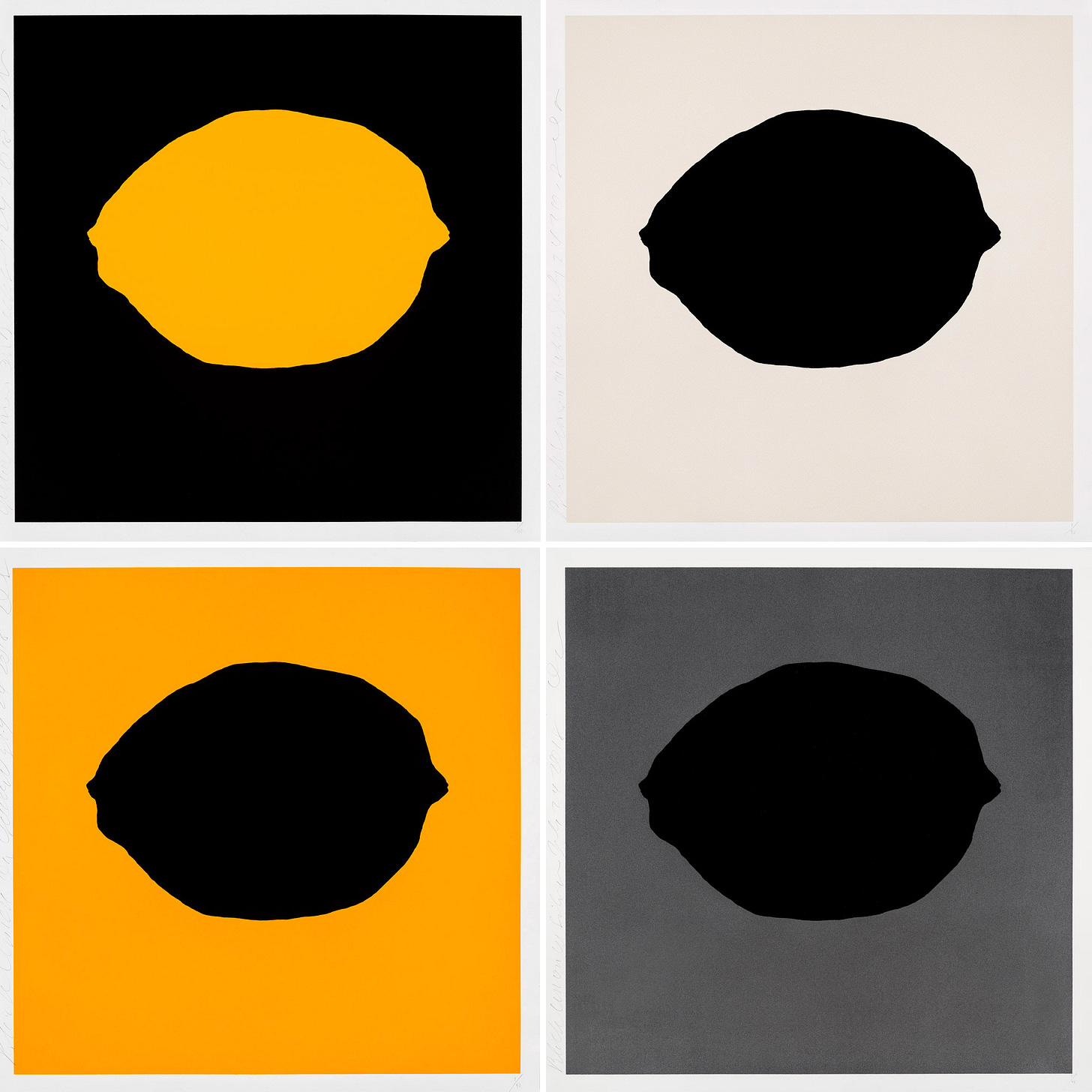

I particularly love the final stanza. The phrase “crisp sun-saturated redolence” less evokes a lemony scent than it replaces it with a different kind of sensuosity, a fullness in the mouth, whose sibilants and liquids practically start me salivating. Stallings waits until the very end to break her metrical pattern. She has lengthened the final line to a trimeter, as if this penultimate feat of verbal imagination has gotten her one step closer to the heroic quatrains the poem would heal to with olfaction restored. The final simile is ingeniously synesthetic—the yellow of the lemon conjures the brightness of the sun in eclipse, while the dark center visually suggests the absent sense. At the same time, and for the only time in the poem, Stallings denies us an exact rhyme, giving us instead a lapsus linguae sort of metathesis, with “crisp / eclipse,” bringing us as it were one step forward and a half step back. No, she seems to say, words and imagination are no replacement for the five senses; they are not adequate, but they are something—just as living on in poetry is not life, exactly, but is also not nothing.

I can think of a few, though not many, other poems in this stanza which might justify my idea that, whether or not it alludes to Sappho, the curtal fourth line is suggestive of a sudden or premature ending of some kind. Two sound examples include “Tarantula, or the Dance of Death” by Anthony Hecht, about the Medieval dancing plague, and Richard Wilbur’s early poem “The Walgh-Vogel,” about the Dodo (the name means “nasty bird” in Dutch and is what the Dutch sailors who first discovered the Dodo dubbed it). Instead of those elder statesmen I’ll quote one by Matthew Buckley Smith of Sleericketts notoriety, who has written several poems in this stanza in his astonishing book Mid-Life. This one describes the breast-feeding of his daughter on a university campus among monuments chiseled with proud, disregarded names (one of which, lurking somewhere behind the rich 19th C donors and the poem itself, might be Sappho’s). The curtal stanza suggests the hard, often sudden stop at the end of each generation, while the syntax, which runs unbroken from the beginning of the poem to its end, suggests the continuous thread of life connecting each generation to the one before and the one to come:

Posterity

by Matthew Buckley SmithThe great remembered man whose name is stone

Over the double doors where students pass

Today is remembered for his name alone,

On the way to class,By those whose names, being something less than great,

Someday will be remembered even less,

By others, also young and running late,

In different dress,And then, as now, sunlight will mark the lawn

And August will sigh the syllable of fall,

Considering the generations gone

Scarcely at all,As scarcely as we consider those to come,

Among our busy thoughts of work and rest,

As scarcely as the seeding in the womb

Considers the breast,Which you, no longer shy, bare to the day,

Here on this quiet campus garden bench,

For our girl, who soon enough will thirst in a way

We cannot quench.

Most enjoyable - and thanks for the intro to the Stallings poem, which was new to me.