Some Versions of Bucolic

Is there a difference between bucolic and pastoral? Plus two contemporary examples

Is there a difference between pastoral and bucolic? A simple question, which has no simple answer. Or, rather, the answer which seems truest to me is also the simplest: No. There is no real difference. “Bucolic” is a Greek word which has to do with cowherds (or “neatherds”), while “pastoral” comes from a Latin word which technically refers to any kind of herdsmen (pascor means “to graze or pasture”), though it’s usually used to mean “shepherd” instead of the more precise opilio. “Bucolic” appears as a literary or generic term as early as Theocritus — his herdsmen say things like “Let’s bucolize!” meaning “Let’s sing some herdsman-songs!” and address the boukolikai Moisai, the “bucolic Muses.” On the other hand, it’s unclear when pastoralis takes on its generic as opposed to its descriptive sense (viz., “relating to pastoral poetry” vs. “relating to the herding of sheep or other animals”). Nonetheless, it is fair to take pastoralis as the Latin translation of Greek boukolikos, as Vergil’s Eclogues translate and Romanize Theocritus’ Idylls, and use the terms interchangeably.

The mind, however, abhors a synonym and will imagine difference where none exists. I think this is what Bakhtin is talking about when he says that a word shapes “its own stylistic profile and tone” in a “dialogized process.” Previously I mentioned having read an excerpt from Discourse in the Novel with blank incomprehension, but I kept at it, and perhaps gleaned something in the end. Bakhtin says:

The word is born in a dialogue as a living rejoinder within it; the word is shaped in dialogic interaction with an alien word that is already in the object. A word forms a concept of its own object in a dialogic way.

“Bucolic” and “pastoral” are in dialogic relation; there is a mental territory they must divvy up between them, but the job is complicated by hundreds of years of generic development and critical disagreement. In the absence of consensus, I would tentatively suggest distinguishing them in one of two ways: first, we could look to our two figureheads, Theocritus and Virgil, and use the term “bucolic” if we consider a given work more Theocritean, or “pastoral” if it seems more Virgilian. In practice we would probably make this distinction along an axis from “earthy” to “sophisticated,” i.e., an idyll or eclogue which treats its rural subjects with a degree of simplicity and rustic realism might be classed as “bucolic,” while one which idealizes and intellectualizes might be considered “pastoral.” “Pastoral” in this sense would be seen to hold sway from the Eclogues through the 18th century, while bucolic would describe Theocritus’ pre-Virgilian imitators then go underground in the first century BCE, to emerge again in the 19th.

Alternatively, we could look to a passage from René Wellek and Austin Warren’s Theory of Literature and use “bucolic” to designate the “outer form” of the eclogue while “pastoral” could designate the “inner form:”

Genre should be conceived, we think, as a grouping of literary works based, theoretically, upon both outer form (specific metre or structure) and also upon inner form (attitude, tone, purpose—more crudely, subject and audience).

Since “pastoral” is so often called a “mode” rather than a genre—there can be pastoral eclogues, epigrams, dramas, and romances, for example—and defined in such general terms that almost anything can be made to count (e.g., Empson’s “putting the complex into the simple,” or Poggioli’s “double longing after innocence and happiness”), it might make sense to let “pastoral” refer vaguely to anything which seems “conceptually pastoral” while using “bucolic” to refer to a work which is “formally pastoral,” i.e., it employs the generic markers and motifs found in Theocritus, Vergil, and the tradition they gave rise to.

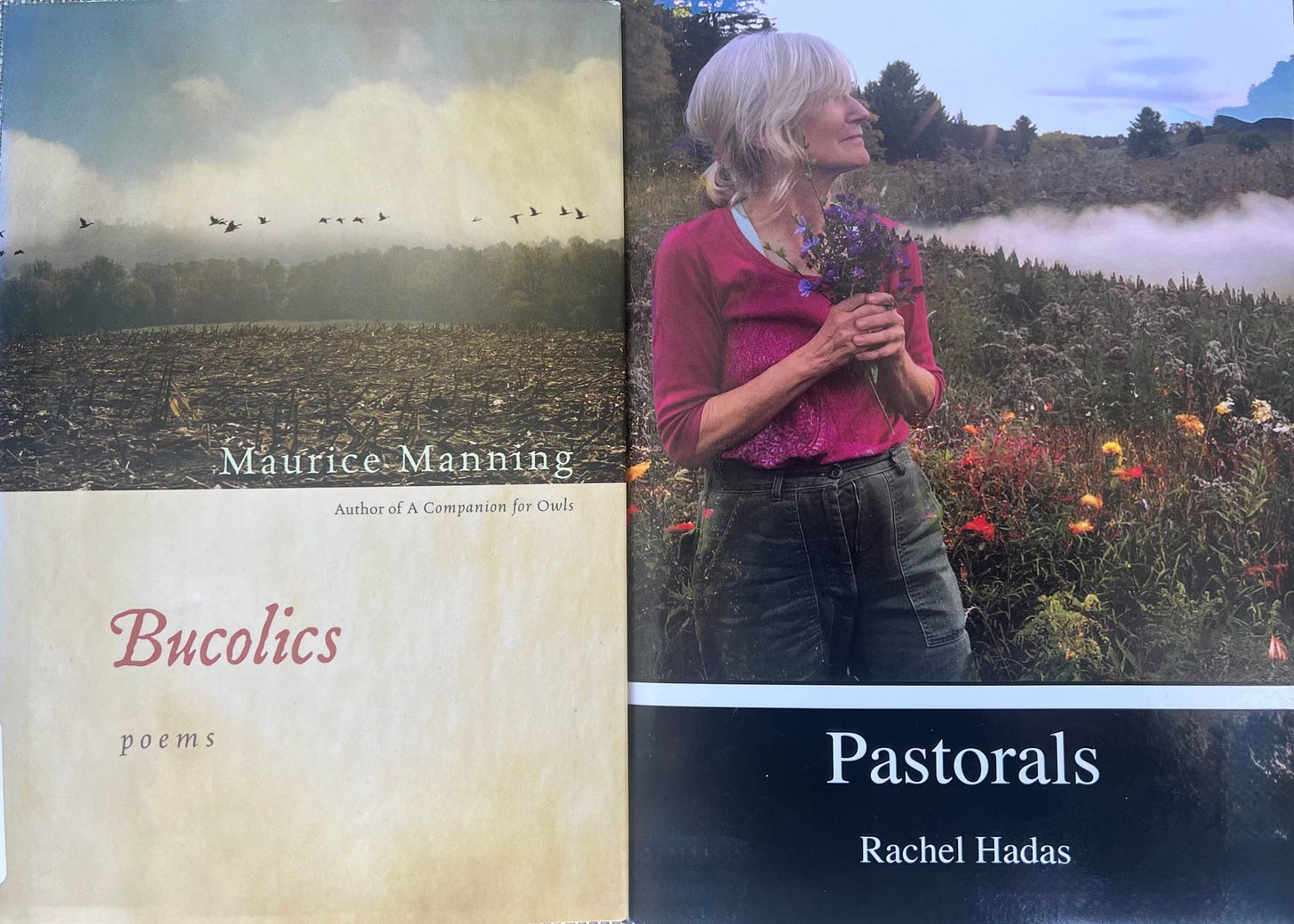

These two alternative distinctions might be useful in thinking about two contemporary entries into this tradition, Maurice Manning’s Bucolics (Harcourt 2007) and Rachel Hadas’s Pastorals (Measure Press 2025). The two books are more different than alike, though a few similarities hold: both feature more or less isolated speakers inhabiting a rural landscape while confronting their human situation. Both also employ the “slice of life” effect of traditional pastoral / bucolic, where the scenes are more exemplary than dramatic, and significance accrues more from the book’s world-building than from anything specific that happens in it. (As I discuss here, one reason for denying that the poems in North of Boston are eclogues is that Frost ups the dramatic ante on the traditional low-stakes pastoral.) The poems in these books thus do not really strive for or attain the splendid isolation of the achieved lyric, which regards the pages that happen to surround it as a matter of indifference; rather, they lean against each other companionably, each one adding a location or situation or adumbrating a mood, recording variations of inner and outer weather over time. Both books are, finally, what I might call “lyric” rather than “dramatic” pastoral or bucolic, since each presents its world through a single lyrical lens. In Bucolics, there is in fact only one human present in the entire book, a nameless field hand/shepherd engaged in a continual one-way conversation with God, while in Pastorals other people besides the poet do crop up, but they’re there more as a ‘daily new furniture of friends’ and family (to adapt Marvell) rather than active characters.

Hadas’ and Manning’s respective books fit both of the proposed distinctions between Pastorals and Bucolics above. When it comes to the rusticity or sophistication of their speakers, Manning’s book is more Theocritean and Hadas’ is more Virgilian. According to Empson,

The essential trick of the old pastoral, which was felt to imply a beautiful relation between rich and poor, was to make simple people express strong feelings (felt as the most universal subject, something fundamentally true about everybody) in learned and fashionable language (so that you wrote about the best subject in the best way).

In truth, neither book does this, no doubt because the modern sensibility, fed so long on realist novels, has grown uncomfortable with country folks speaking like courtiers; it punctures what John Gardiner calls “the dream of fiction.” Manning’s Kentucky field hand, therefore, speaks in the patois of a Kentucky field hand—at least, he uses plenty of homely turns of phrase meant to convey rusticity, starting with the most insistent word in the poem, “Boss,” which is what his speaker calls God. Moreover, Manning’s lines are unpunctuated, making them seem both less educated and less page-bound than would otherwise be the case. Hadas’s speaker, on the contrary, being a classicist-poet-professor aestivating in a familial estate, talks like Rachel Hadas (is Rachel Hadas), seasoning her sentences with lots of quotations from poetry and lots of Latinate diction. The city, too, is much more of a presence (albeit an offstage one) in Hadas’s Pastorals than in Manning’s Bucolics, just as Rome casts a longer shadow over Vergil’s Eclogues than Alexandria over Theocritus’ Idylls. In formal terms, while Hadas is a poet of great formal dexterity, Pastorals is written in prose, calling to mind not so much Virgilian eclogues or Theocritean idylls as Renaissance pastoral romances, like the Arcadias of Sannazaro and Sydney. Manning’s Bucolics, however, are versified in mostly tetrameter iambic lines which spill in stream of consciousness down the page; formally, therefore, they have a lot more in common with the bucolic monologues of (e.g.) Idyll 11 and Eclogue 2. On these grounds at least, and relative to each other, it seems to me that both books are aptly enough titled.

There is however one glaring (albeit trivial) infelicity to the title Bucolics, which is that there are no cows or oxen anywhere (remember that boukolos means “cowherd”). There are some occasional lambs, which I suppose is why in interviews Manning refers to his speaker as a “shepherd,” but he really seems to be more of a farmer / field hand, making the book technically more georgic than bucolic. This is how poem XXV begins (all the poems have Roman numerals for titles):

I guess you’ve got a lot

of hands though I’m just one

of many Boss I’ll turn

the dirt I’ll shock the corn

As I mentioned elsewhere, Theocritus does have one ‘georgic’ poem about reapers, but general farm work is basically not bucolic activity. This bit of pedantry is doubtless of little interest to Manning, who admits to Brian Brodeur in Literary Matters that he was not really reading either Virgil or Theocritus while working on the book. In poem XIII his shepherd seems to be shoeing horses, in XLI he’s moving rocks and clearing the field for plowing, in XLIV he is probably dressing vines, in LIV he’s making hoops to repair a barrel, in LX he’s hoeing, and in LXIII he’s pitching hay. In this limited sense his book might be as accurately (though less expressively) titled Georgics.

On the other hand, Manning’s book does employ distinctly bucolic motifs, notably, the country simile. Here are a couple examples from Theocritus and Vergil. The first passage gives the opening of Polyphemus’ song in Idyll 11; the second is from an ‘amoeboean’ competition (shepherd rap-battle / flyting match) between Damoetas and Menalcas in Eclogue 3:

My Galatea, fair and shearling-soft,

firm as an unripe grape, as white as cream,

and shyer than a calf, why blow me off?

For you won’t come ashore but while I dream,

and when the dream lets go, you run away,

as a sheep flees a wolf that’s after it. [Theoc. Id. 11]Damoetas: As lambs at wolves, ripe wheat at storms, and trees

at winds, I quail at Amaryllis’ bile.

Menalcas: As rains please seeds, shrubs goats, as willows please

expectant ewes, Amyntas makes me smile. [Vi. Ecl. 3]

There are a bunch of examples of these kinds of “country similes” in Manning’s Bucolics. Here are some:

you’re like a rooster Boss if you

had just one feather left you’d strut

around the barnyard [XXIII]you move in every direction

at once you’re worse than

the wind Boss worse than

a rock dropped in the water [XXX]the flower has a little night

inside it I can see it Boss

a drop of pitch a pinch of sleep

as if the flower wants the night

to last a little longer than

it does I’m like the flower Boss [LXXII]

These examples range from bathetic (the rooster) to profound (the flower, with echoes of George Herbert, who is a guiding spirit of the book) but all serve to characterize Manning’s speaker. There is another, related device which does even more work as characterization. I think of it as a variation on the country simile, albeit in the interrogative mood — the speaker pictures God in his own image, and asks him if he does or has this or that thing the speaker himself does or has:

what color is your collar Boss

is your backbone sore from bending over

when you clap your hand against your thigh

does a little cloud of dust fly off

do you wipe your face with your shirttail Boss

I’d bet my wages that you do [IV]

Naturally, these passages (and there are a bunch of them) call to mind a non-bucolic bit of Greek philosophical verse, from Xenophanes:

But if oxen had hands, or horses, or lions had them,

or could draw with their hands and make art like the art of humans,

the horses would make their deities look like horses,

the oxen would make them like oxen, and each would design

their gods with the same sort of bodies they have themselves.

Again and again Manning shows us his shepherd questioning God about his likeness to himself and struggling to wrap his mind around their differences. The manoeuvre is psychologically astute and, it seems to me, an effective expansion of the “country simile” motif.

I have more mixed feelings about the use of country diction. I don’t mind it in principle, but the more a word or phrase calls (potentially cringeworthy) attention to itself, the more I want it to defend its position with some further justification. “Boss” is the most prominent example. As you’ve already guessed, it appears a lot and I won’t say it never gets annoying. However, in my opinion it mostly works, because of a sort of double meaning: besides the primary sense of “superior,” “overseer,” “foreman,” “boss” is indeed a southern-inflected synonym for “buddy,” which carries an amused or dismissive air of ironic deference—at least, that’s how I’ve interpret it when I’ve rented a cabin in West Virginia for the weekend and the overall-wearing dude at the counter of the general store calls me “boss” when I go to buy a plastic lighter or something. Anyway, this sense of an ironic edge in “boss” tempers somewhat the shepherd’s solitary servility with a bit of rebellious human bluster.

But the rustic idioms work best when Manning is able to use the context to give them some extra resonance. For example, addressing God’s sense of humor, he says, “you sneaky devil you cutup Boss.” Boss is more an immanent than a personal God, so this light identification with the devil feels felicitous. The next poem begins “you’re the hay maker Boss” which works in three senses—he literally makes hay, but also he is a “cutup” (“make hay while the sun shines,” i.e., have your fun while you can) and he packs a punch. There are a number of further examples I could cite, but here is the end of poem LXIV, about Boss’s essential elusiveness:

I pick you up I put my hands

around you Boss I know my face

won’t fit inside the scene there’s so

much nothing Boss it makes me think

there’s nothing to it but listen now

I’m looking over you so if

I told you I was thirsty would

you shrink I wonder Boss if all

at once I swallowed you O tell

the truth how would that grab you Boss

What I admire here is the double resonance of the final question. Its idiomatic meaning is “how would you like that?” but in context the question is genuine—how would that grab you? The answer is that it wouldn’t; Boss would continue to be ungraspable.

Yet it is very easy to hit a wrong note with this kind of thing, and a number of these ‘bucolisms,’ which lack irony or extra resonance, strike me as intolerably cutesy and twee:

you can be the slowest poke

you old molasses boss [XLI]would you trade hee-haws with a crow

would you ever sit back Boss to let

a crow go gitchy goo on you

those crows they’re always cutting up [LXX]

Everyone’s mileage will vary, and no doubt some will have less patience than I do, while others will have more. It may be that moments like these lend Manning’s speaker a bit of an air of the clod or clown (“man of rustic or coarse manners, boor, peasant”) and so opens up what Empson calls the “double attitude of the artist to the worker, of the complex man to the simple one (‘I am in one way better, in another not so good’),” which is also how Empson says Milton feels toward Adam in Paradise Lost. There is also something of the visionary to Manning’s field hand, and he occasionally rises from plaintive hectoring to something genuinely frightening:

I know it Boss it burns me now

to smell the smoke like burnt light shook

right from the burning tree is this

the kind of light you might call last

will I smell smoke before you shake

the light from me before you pinch

my little flame into a hiss

All characteristics of “bucolic” or “pastoral” aside, the single most affecting feature of this book is its decision to portray one human being and one only, in perfect isolation except for farm animals and implements, speaking constantly, rambling even, crying to the void with no response. He is in a kind of wide-open solitary confinement, and flirts, as any of us might in such circumstances, with both the ridiculous and the sublime.

Hadas’ Pastorals is a more civilized affair. It is really less of a Virgilian pastoral than a personalized book-length country house meditation in the tradition of Jonson and Marvell. This passage from Tom Thumb, quoted in Empson, was relevant enough for me to copy it into the front of the book:

Corneille recommends some very remarkable day wherein to fix the action of a tragedy. This the best of our tragical writers have understood to mean a day remarkable for the serenity of the sky, or what we call a fine summer’s day. So that … the same months are proper for tragedy which are proper for pastoral.

In Vermont, where Hadas’ country house is located, fine summer days seem mostly to be what she gets, despite occasional rains; winter happens elsewhere. The tragedy is light, a hint only, a whisper in the summer breeze, where nonetheless Hadas, 76, senses “Time’s winged chariot.” Yet, as Hadas writes, sometimes “lightness weighs heavy” (“Those Flannel Nightshirts”). The sadness is mild, but it is there, as when following a Fourth of July fireworks display a child is heard to ask, “Was that all?” Its hub is the generous, ramshackle old manse, which seems to have been part of the Hadas family all her life. For her, it is a “kaleidoscope” and an “anchor” and a “Pandora’s box of needs:”

There was the big attic, its corners piled with boxes whose ripe, half-forgotten contents promised to yield surprises. There was the bed I kept returning to, its faded quilt, the cats coming and going, now on a chair, now in the cat loft, now curled up between my beloved and me. The old house, the rain, the seasons, the years, the time, the memories. Past summers came and went like the rain, now tempestuous, now gentle as a mist. [“Orchard, Medallions, Owl”]

In the poems, which blend into each other like summer days, she describes the “scrubbed attic full of books” and the writing “table where I sit and look out through the screen at the garden.” She reflects on the different views from each window, the various way the light falls in each. From her screened porch, she watches a phoebe family, which poops on her writing table. “None of the doors in the house shuts tight.”

That still unfinished cabin, that chained hound daily baying—these are not merely scenery we pass. They’re also where we live. Take my house: it has a new red roof, but inside something’s missing. Something is always missing. And something else is present and abundant. [“Walk with Elephants”]

The house is a kind of Ship of Theseus, with every old plank swapped out more than once. In “Summer Variations II” Hadas describes, at a level of detail I find surprisingly moving, how rooms have changed over time, converted from bedrooms to studios and back, and old beds have been bought and jumped on and replaced and sent to the attic. She quotes Keats:

The careful monks patch and patch it till not a thread of the original fabric is left, but still they show it for St. Stephen’s shirt.

The house is also full of ghosts, as in De La Mare’s “The Listeners.” It passed to Hadas from her parents, both classicists: her mother was a Latin teacher and her father, Moses Hadas, was a popular classics professor and presenter and a deeper scholar than those who claim a similar public role today. Rachel reflects movingly on Moses’ life in this essay from 2001. He was an indefatigable translator of the “clean and clear” school and an energetic popularizer, who advocated teaching Classics via literary criticism as well as, or instead of, philology, and is one of the main reasons Classics departments today offer “Classical Literature in Translation” classes in addition to readings in Greek and Latin. (I wonder how he would have felt about Princeton’s 2021 curriculum change allowing students to major in Classics without ever studying the languages.) He was also a charismatic teacher whose course on Greek Drama at Columbia enchanted a 23 year-old John Ashbery, as we learn in Pastorals.

Moses and his wife are ghosts in Pastorals, albeit companionable ones. Their daughter imagines

my mother on her knees weeding, or pacing slowly, almost drifting … trailing a few blades of grass or an uprooted weed in one hand. Have I become her? … Or my father, sitting at a rickety table on the porch or in the barn, typing with two fingers—have I become him? [“Summer Variations II”]

For let us say personal reasons, I am interested in these glimpses of the famous classicist, of which we only get a few. We learn of an old bed he purchased from “Penniman’s junk store” eventually destroyed by Rachel’s son jumping on it. We hear about a book he wrote in 1960 (I’d guess this one), apparently not one of his best, which Rachel at one point struggles to read. Moses’ elusiveness may relate to his workaholism. As Rachel wrote in 2001: “Hadas's life was his work. True, he was a loving if weary father whose death when I was seventeen shook me for many years but whose life influenced mine in innumerable ways. … [M]y father knew how to work but not how to rest. Rest turned out to amount to death; but death was not a cessation.” For me, the following passage may be the most moving in the book:

I wish I’d asked my father more questions—not actuarial questions but endless other questions. I want to reach out and back over the years, to somehow stretch across the strumming silence and say “I think maybe I know. I’m in that territory now. How was it for you? How did you manage it?” If he answered me, we might be able to compare notes. But mostly I hope I’d want to stay quiet, if I could do that—stay quiet and listen. [“Endless Other Questions”]

The pages of Pastorals give evidence of both work and rest. This book is, to judge from the list on Hadas’ website, her twenty-eighth, and another is apparently due out this year from Able Muse Press. Perhaps her immense productivity was a lesson she learned from her father; it seems clear anyway that she has used her constant writing practice (as well as her poetry editorship of The Classical Outlook) to stay busy in retirement, happily avoiding the fate she ascribes to him. Yet there is also relaxation in Pastorals: its form (prose) is easy-going and compendious, accommodating daily bric-a-brac and trivialities, as when we get two paragraphs about an unspecified obligation which Hadas must pull out from over email. Its mood is by turns languid and nostalgic, rueful and grateful. It is more of a daily journal recording what occurs than an exacting distillation of an essence. Hadas seems to acknowledge this easing of intensity in a poem curiously titled “Black and White: Suspension Bridge:”

One eye blinks tell, the other winks distill. Reach out, Tell says. Build a suspension bridge of narrative experience can cross, finger-walking its hand along the railing. … Under the bridge, far below, a river is running.

All this is known already, says Distill, so you can leave most of it out. Delete. Compress. Transform.

My tastes run toward distillation, and I wish Hadas had done a bit more of it. I’d generally rather sip whiskey than brook-water unless the stream is very pure. Yet here, something in the candidness and occasional prolixity of the style makes it feel as though Hadas has opened her house to us just as it is, with dirty dishes in the sink and bird poop on the writing table. Her pastorals are homey and hospitable, and she is a thoughtful and intelligent host.

The book is not too relaxed to produce phrases and passages I admire. Two spiderwebs hanging over a brook are described as “twin systems kissing lightly in midair.” In the looks of one of Moses’s great-grandsons Hadas perceives “echoes in the bone.” And, in “Storing the Season,” she writes of making preserves, jams and applesauce, to hoard the richness of summer as what elsewhere, in a Wordsworthian vein, she calls “food for winter:”

The problem is the prodigality: apples and blackberries in profusion, both fruits by their respective natures hard to reach. Tangle of brambles, berries glossy black: even to graze them with a fingertip, you have to stretch over a jungle of thorny vines and balance on a rotting log. Rosy apples cluster like the bride in Sappho at the tip of a branch too high to reach. [“Storing the Season”]

Perhaps the first sentence might feel less cluttered if she had written “naturally” instead of “by their respective natures.” Even so there is a Heaneyesque lushness to these lines which waters the mouth. Because it’s what I do in this news-free letter, I’ll give my translation of the Sappho poem Hadas alludes to, which she reads plausibly as a fragment of an epithalamium:

105a

An apple on a bough hangs redly, sweetly,

high on the highest limb, against the sky.

The pickers leave it be, but don’t completely

leave it—they reached for it; it was too high.

It is fitting that Sappho should crop up near the end of Pastorals, so much of which is about inheritance, personal and poetic. Hadas knows well that apples are love-gifts in classical poetry, as in this epigram falsely attributed to “Plato:”

I am an apple, fruit of your lover’s praying.

Say yes, Xanthippe. We are both decaying.

They are also common in pastoral. In this passage from Vergil’s Eclogue 8, the shepherd Damon falls in love with Nysa as he and his mother take her to pick apples:

I saw you as a child—I was your guide—

with mother picking apples on our land.

I was just twelve, and able, if I tried,

to snap the bottom branches with my hand.

I saw, and I was lost. That’s when I died.

Like many a pastoral poet before her, Hadas spends plenty of time picking apples; the difference is perhaps that she uses them to make applesauce. For her,

Each apple is both end product and embryo, rich with seeds, full of promise[.] … Each apple is also a sweet synecdoche, a condensation of many apples, a distillation of past summers. [“Applesauce”]

You can say the same about the poems in Pastorals.

Enjoyed this—the pastoral genre doesn’t ever seem to finally exhaust itself. The excerpts from the two contemporary examples were somewhat underwhelming, though—the “boss” usage has a novel appeal for sure but it’s hard to imagine it not getting tedious across a whole book. The Theocritean spirit shows up in all kinds of surprising places, such as Mary Ruefle’s short prose piece “They Were Wrong”

https://hyperiondays.substack.com/p/on-gardens-or-the-life-in-mary-ruefles?r=2fj4o4&utm_medium=ios&triedRedirect=true

Virgil originally called his Ecologues Bucolia, “cowherd songs” after Theocritus but in the sense of the pastoral. The Georgics in contrast were about farming (“a life that knows no fraud”) and bees and their city state (“When they swarm it is advisable to attract them with scents and the clashing of cymbals”). The last lines of book IV of the Georgics (my old Faber edition) do note, “I, Virgil, in those days was more concerned with the songs of shepherds.”