Having dipped into Callimachus last week in the most Callimachean way possible, via an obscure fragment from his Aetia about the invention of the mousetrap, I thought I would stick with him here but shift to his most famous poem, at least in English—his elegy for his poet-friend Heraclitus. It must be noted this Heraclitus is not the Ephesian pre-Socratic philosopher who remarked that “Upon those who step into the same rivers different and again different waters flow” (ποταμοῖσι τοῖσιν αὐτοῖσιν ἐμβαίνουσιν ἕτερα καὶ ἕτερα ὕδατα ἐπιρρεῖ), more popularly remembered as “You can’t step into the same river twice,” but rather an almost entirely unknown poet from Halicarnassus who lived a couple centuries after the great aphorist. Callimachus’ epigram is famous in English because of a translation by a beloved and disgraced Eton schoolmaster, William Johnson Cory:

εἶπέ τις Ἡράκλειτε τεὸν μόρον, ἐς δέ με δάκρυ

ἤγαγεν, ἐμνήσθην δ᾽ ὁσσάκις ἀμφότεροι

ἥλιον ἐν λέσχηι κατεδύσαμεν: ἀλ̀λὰ σὺ μέν που

ξεῖν᾽ 'Αλικαρνησεῦ τετράπαλαι σποδιή:

αἱ δὲ τεαὶ ζώουσιν ἀηδόνες, ἧισιν ὁ πάντων

ἁρπακτὴς Ἀίδης οὐκ ἐπὶ χεῖρα βαλεῖ.They told me, Heraclitus, they told me you were dead,

They brought me bitter news to hear and bitter tears to shed.

I wept, as I remembered, how often you and I

Had tired the sun with talking and sent him down the sky.

And now that thou art lying, my dear old Carian guest,

A handful of grey ashes, long long ago at rest,

Still are thy pleasant voices, thy nightingales, awake;

For Death, he taketh all away, but them he cannot take.

A while back my friend and mentor, A.E. Stallings, posted a wonderful appreciation of the beauties of this translation which I could not hope to better. She notes that, while Callimachus’ Greek possesses a ‘classical’ restraint, Cory’s translation is more highly colored and emotional: “The Greek is like pure, transparent spring water. The English is like a vintage claret.” She points out that Cory’s version is in hexameters, except for the two lines of greatest emotion, 2 and 8, which are fourteeners, and notes felicities where others might tot up infidelities: “Carian,” instead of “Halicarnassian” (Caria is the region in which Halicarnassus was located) is both metrically convenient and sounds like “carrion;” “a handful of grey ashes” expands on one word in Greek, σποδιή, but gestures at the “hand” (χεῖρα) of Death in the last line; and even “thy pleasant voices,” which is Cory’s addition, is derived etymologically from the Greek word for “nightingales,” ἀηδόνες, from ἀείδειν, ‘to sing.’ Verse translators need to be able both to compress their originals and, at times, to expand them plausibly; these expansions from Cory are masterful and reveal him intimately in tune with his original.

In my own translation of this poem, I did not want to compete with the power of Cory’s version so much as to reach back for a little more of that classicizing restraint which he emotes away. At the same time I wanted to convey my debt to his version. This is what I came up with:

When I heard, Heraclitus, you were dead,

I thought of all the suns we’d talked to bed

those nights, and the tears came. Dear guest, I know

that you were ashes long and long ago,

and yet your nightingales are singing still:

Death kills all things, but them he cannot kill.

Whether you prefer the emotional expansiveness of “They brought us bitter news to hear and bitter tears to shed” or the understatement of “and the tears came” will likely depend on your own sensibility. At any rate this little number from my book has been mentioned in at least two different reviews. In the Telegraph Stallings calls it “solid” and says it “wisely wink[s] at the famous version,” while in the PN Review the ever thoughtful and interesting Victoria Moul (subscribe to her Substack if you haven’t already!) pans it as “pastiche.” I’ve been mulling her critique and have come up with a couple alternatives that wink less, of which I’ll share one. Feel free to comment and let me know if you think I’ve made it worse or better!

When I heard, Heraclitus, you were dead,

I thought of all the suns we’d talked to bed

those nights, and the tears came. Dear guest, although

the ashes claimed you many years ago,

your nightingales have never ceased to sing:

Death can’t catch them, who catches everything.

(Victoria rightly laments my failure, which I also regret, in the final couplet of both versions to imitate Callimachus’ enjambment on ὁ πάντων / ἁρπακτὴς Ἀίδης, which means something like “the all- / ravishing Death;” “of all” (πάντων) is dangled at the end of the line and then snatched away by ἁρπακτὴς after the line break.)

But back to Cory, a man about whom, this one translation apart, I knew nothing before starting this post. I now know more than I would like to, though be it noted that the precise nature of his error at Eton, which rumor holds to have been Callimachean indeed, is shrouded in secrecy. Wikipedia however also quotes from his defense of a rigorous secondary education, which I want to reproduce here because I think it’s brilliant:

At school you are engaged not so much in acquiring knowledge as in making mental efforts under criticism. A certain amount of knowledge you can indeed with average faculties acquire so as to retain; nor need you regret the hours you spent on much that is forgotten, for the shadow of lost knowledge at least protects you from many illusions. But you go to a great school not so much for knowledge as for arts and habits; for the habit of attention, for the art of expression, for the art of assuming at a moment's notice a new intellectual position, for the art of entering quickly into another person's thoughts, for the habit of submitting to censure and refutation, for the art of indicating assent or dissent in graduated terms, for the habit of regarding minute points of accuracy, for the art of working out what is possible in a given time, for taste, for discrimination, for mental courage, and for mental soberness.

His emphasis on “arts and habits” over “content” is resonant and redolent of that pedagogical progressiveness which might have been what got him sacked, if it wasn’t impropriety. However, what really strikes me here is the phrase “the shadow of lost knowledge,” which haunts all of us who devote ourselves to classical literature. In this context, my mind goes straight to the nightingales of Heraclitus, which (pace Callimachus) have ceased to sing, and (pace Cory) are awake no more—all, that is, except this one:

ἁ κόνις ἀρτίσκαπτος, ἐπὶ στάλας δὲ μετώπων

σείονται φύλλων ἡμιθαλεῖς στέφανοι

γράμμα διακρίναντες, ὁδοιπόρε, πέτρον ἴδωμεν,

λευρὰ περιστέλλειν ὀστέα φατὶ τίνος. —

ξεῖν᾽, Ἀρετημιάς εἰμι: πάτρα Κνίδος: Εὔφρονος ἦλθον

εἰς λέχος: ὠδίνων οὐκ ἄμορος γενόμαν

δισσὰ δ᾽ ὁμοῦ τίκτουσα, τὸ μὲν λίπον ἀνδρὶ ποδηγὸν

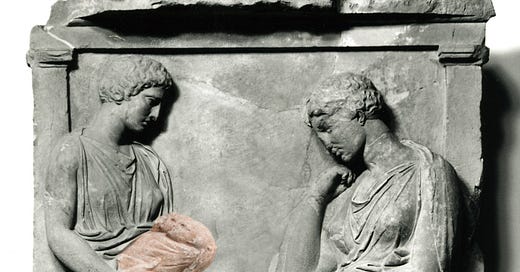

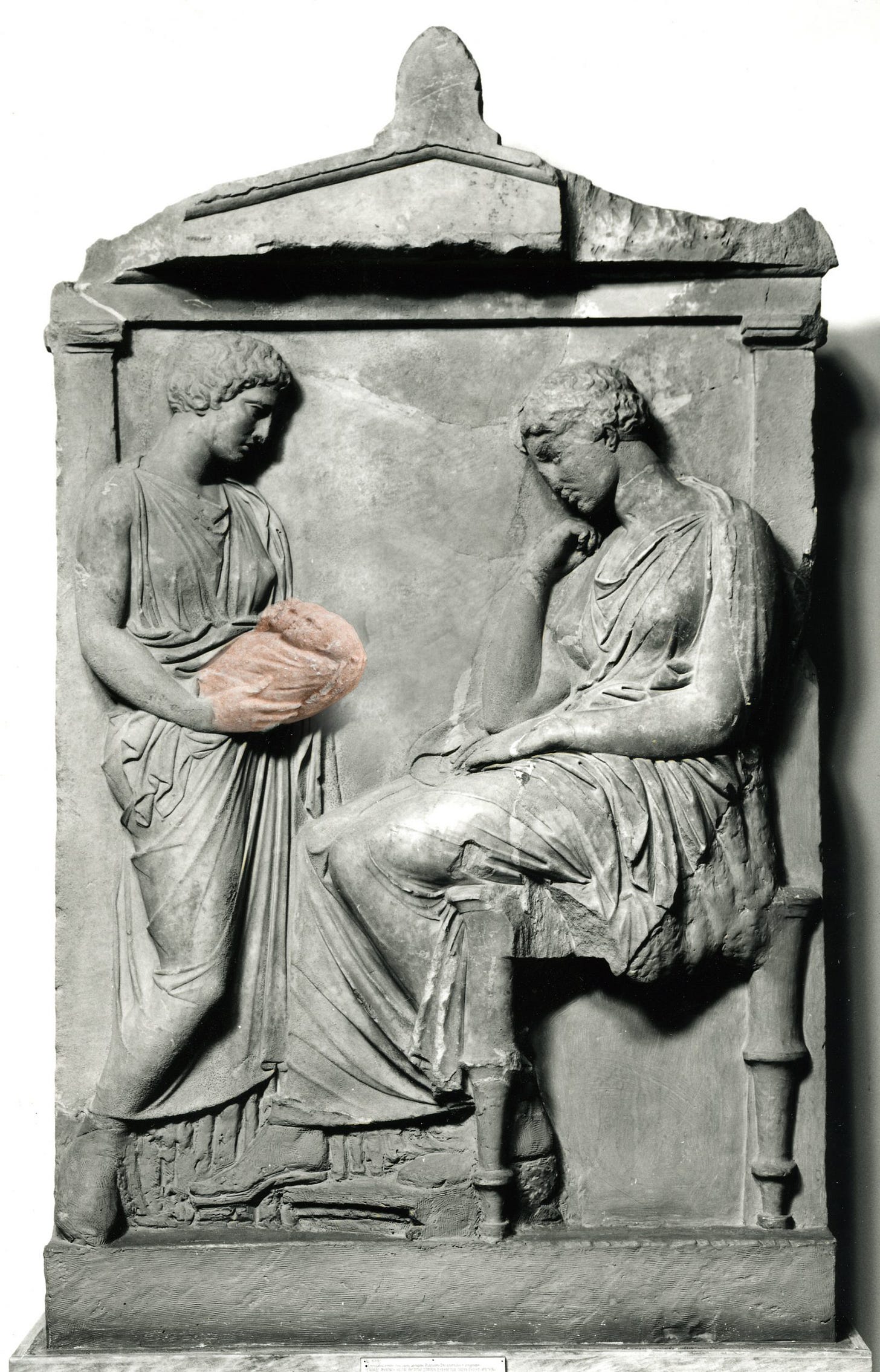

γήρως: ὃν δ᾽ ἀπάγω μναμόσυνον πόσιος.The earth is freshly dug, and the leaves wave

and drop from garlands draped about the grave.

Traveler, come, let’s read the stone and find

whose scoured bones it says are here enshrined.

‘I’m Aretemias, kind Euphro’s wife,

from Cnidus. Birthpangs brought me twins in life:

one helps my husband in infirmity;

one, to remind me of him, came with me.’

I prefer your first translation; it seems to offer more restraint (which is more comfortable for me). As do you, I love Cory’s defense of education, as applicable to STEM as to literary study. The last poem is lovely as well.