Last week I touched again on Callimachus, the father of the “slender” (leptos / tenuis) Alexandrian school, who had enormous influence on Roman poetry, most explicitly on Catullus and Propertius, but implicitly on Vergil, Horace, Ovid and the whole gang: (

Moul’s thoughtful review of my book points out, not uncritically, how my fascination with Callimachus as a “hinge” between Greece & Rome weighs heavily on the overall emphasis and selection.) At the same time as I was sipping pure poesy through a Callimachean straw, published a thunderous piece about the “mighty Olympian” Pindar, “the most wholesome poet we have,” which slathers my own work with disconcertingly fulsome (indeed, Pindar-sized) encomium. I hope you’ll read his essay for its resounding celebration of Pindar’s “blazing Theban sun” if not for his comments on my own work, which I’m too discombobulated by to discuss. (Elijah also showed himself to be perhaps the only person other than me & Ryan Wilson who read this old piece of mine on Nemean 7, a poem I ended up not including in the book; I’ve been thinking about reposting it here, and maybe I will sooner or later.)Callimachus knew Pindar well and was deeply influenced by him, though he was rather far in spirit from the Theban’s “infinite gratitude” and “infinite enthusiasm” which Elijah celebrates. Consider the end of his Hymn to Apollo, where the sea and sea-like Euphrates (“Assyria’s river”) are thought to refer primarily to Homer but could also stand in for Pindaric copia verborum (abundance of words), while the bees sipping holy springs evoke Callimachus’ own less grandiose but more highly finished art:

Envy covertly buzzed in Apollo’s ear:

‘I don’t care for poets whose song is less large than the sea is.’

Apollo kicked Envy away with his foot, and answered:

‘Assyria’s river is vast indeed, but its churning

lymph rolls sewage and sediment down in abundance.

Demeter’s Bees don’t carry her water from any

source – the holy springs they sip at flow slightly

but purely, and theirs is the most exquisite of waters.’

Hail, Lord! Let Criticism slink where Envy slunk to.

Horace’s Pindaric streak was of a piece with Callimachus’: he knows him well and nods to him often, though, like Callimachus, he also disclaims and recuses himself from any high-flying Pindaric ambition. He does this in many poems, but most explicitly in the ode whose first two stanzas Elijah translates in his piece, Ode 4.2. The ode is an example of a popular Augustan form called a recusatio (‘refusal poem’), in which Horace refuses to praise Augustus’ triumphs on the grounds that he is unsuited for such a lofty task; he compliments another poet, Julus Antonius, as a grander talent and therefore a likelier encomiast, though he makes sure to slip in some pretty grandiose praise of his own for good measure.

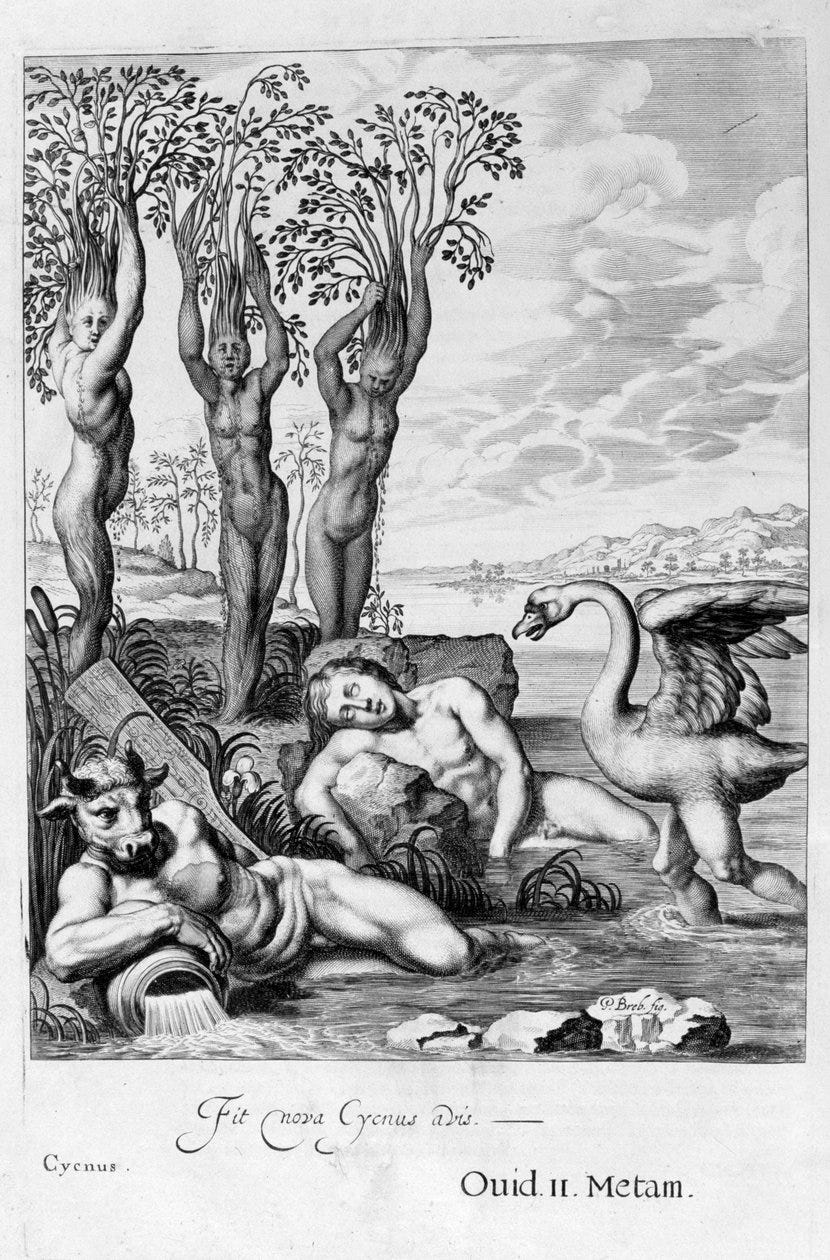

In the ode Horace pays Pindar the tribute of imitation, even while denying that such is possible, chiefly in the way he sends his syntax coursing powerfully down from stanzas 2 through 5, as he lists the major poetic genres Pindar made his own. Note that the epinician (victory ode), the form for which Pindar is most famous today for the simple reason that those have survived in bulk, is only the third of four in Horace’s list, which goes: dithyramb, hymn, victory ode, dirge. Yet while Horace imitates Pindaric syntax, he shies away from Pindaric form; Horace’s sapphic is a much smaller and less demanding kind of stanza than Pindar’s sprawling strophes. Moreover, it is monostrophic, not triadic (Elijah’s piece explains triadic structure if needed), though one may wonder whether Horace even quite understood what Pindar was up to metrically: he speaks of his numeris lege solutis, “meters freed from law / constraint,” suggesting that knowledge of the great archaic choral triads may by Horace’s day already have passed from history.

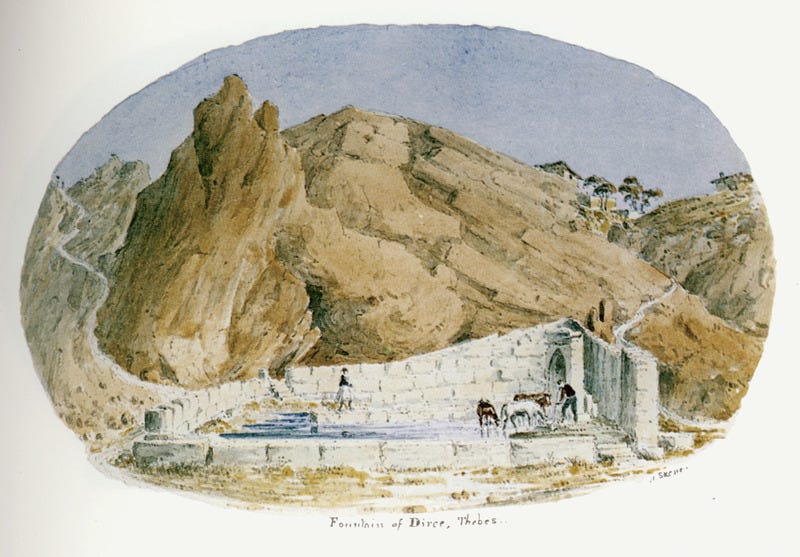

A pivot in the sixth stanza reveals Horace’s Callimachean allegiance by comparing himself to a bee of Mount Matinus, Italianizing Callimachus’ Bees of Demeter, in contrast to Pindar / Julus as the ‘Swan of Dirce’ (Dirce is a fountain in Pindar’s native Thebes). Here we find the ode’s most striking callida iunctura: in line 31, the pointed juxtaposition of operosa parvus, “laborious [songs]” and “[I, being] small.” The word order there does much both to convey the delicacy of detail Horace was after, and to convince us that he sweated over it. After a description of Augustus’ triumphal parade which gestures toward the grandeur Horace disclaims, the ode ends in a quintessentially Horatian diminuendo: Horace conjures an impressive twenty-animal sacrifice which either Julus or Augustus will make — the two penultimate stanzas assimilate Julus’ poetical triumph with Augustus’ military one — while Horace himself will offer what he can, a single baby calf, tawny in color, with a little splash of white between its horns. Horace’s poem therefore manages to be charming and tactful in precisely the manner typical of him; he gets some praise in for everyone concerned (Pindar, Julus, Augustus), and displays enough virtuosity to hint that his refusal of Pindarism derives more from temperament than incapacity. Finally, his conclusion makes an implicit, almost proto-Christian, argument for the value of sincerity over display, as well as of minute attention, and getting the details right. Contemplating his calf, it is easy to forget that Horace’s poem itself is as much a performance and display as anything Julus Antonius might come up with. In fact, one imagines Horace has put Antonius in a pretty tough spot, and that any 800-hexameter encomium will struggle to be as memorable as the white splotch on the head of Horace’s tawny calf.

Ode 4.2

Pindarum quisquis studet aemulari,

Iulle, ceratis ope Daedalea

nititur pinnis, vitreo daturus

nomina ponto.Monte decurrens velut amnis, imbres 5

quem super notas aluere ripas,

fervet inmensusque ruit profundo

Pindarus ore,laurea donandus Apollinari,

seu per audacis nova dithyrambos 10

verba devoluit numerisque fertur

lege solutis,seu deos regesque canit, deorum

sanguinem, per quos cecidere iusta

morte Centauri, cecidit tremendae 15

flamma Chimaerae,sive quos Elea domum reducit

palma caelestis pugilemve equomve

dicit et centum potiore signis

munere donat, 20flebili sponsae iuvenemue raptum

plorat et viris animumque moresque

aureos educit in astra nigroque

invidet Orco.Multa Dircaeum levat aura cycnum, 25

tendit, Antoni, quotiens in altos

nubium tractus; ego apis Matinae

more modoquegrata carpentis thyma per laborem

plurimum circa nemus uvidique 30

Tiburis ripas operosa parvus

carmina fingo.Concines maiore poeta plectro

Caesarem, quandoque trahet ferocis

per sacrum clivum merita decorus 35

fronde Sygambros;quo nihil maius meliusve terris

fata donavere bonique divi

nec dabunt, quamvis redeant in aurum

tempora priscum. 40Concines laetosque dies et urbis

publicum ludum super impetrato

fortis Augusti reditu forumque

litibus orbum.Tum meae, si quid loquar audiendum, 45

vocis accedet bona pars, et: 'O sol

pulcher, o laudande!' canam recepto

Caesare felix;teque, dum procedis, io Triumphe!

non semel dicemus, io Triumphe! 50

civitas omnis, dabimusque divis

tura benignis.Te decem tauri totidemque vaccae,

me tener soluet vitulus, relicta

matre qui largis iuvenescit herbis 55

in mea vota,fronte curuatos imitatus ignis

tertius lunae referentis ortum,

qua notam duxit niveus videri,

cetera fuluus. 60

Julus, no one can rival Pindar. Try,

we're flapping our waxen wings, outsoaring caution,

and bound to drop like Icarus from the sky

and name an ocean.

Like a storm-fed torrent over a steep 5

cliff-face, bursting its banks as it roars along,

Pindar goes hugely thundering from the deep

source of his song,

by merit earning the laurel of Apollo,

whether in his bold dithyrambs, where he 10

rides rapids of new words, and rhythms follow

lawless and free;

or when he hymns the gods and their royal blood,

the kings, who dealt the Centaurs a just death,

and killed the huge Chimera, quenching its flood 15

of fiery breath;

or praises a winning boxer or charioteer,

parading home transcendently wreathed in fronds

of palms from Pisa, gifting him words more dear

than sculpted bronze; 20

or mourns a youth in a dirge while his young bride grieves

and weeps to hear the golden encomium

raising his life to the stars, where he still lives

and thwarts the tomb.

So often, Julus Antonius, blows the breeze 25

lofting the Swan of Dirce into the high

countries of cloud; while I, like the little bees

that bumble by

Matinus’ groves and the wet banks of the Tiber,

busily culling delicious drops of thyme 30

among those foothills, fashion, with heavy labor,

my modest rhyme.

But you, a poet of grander sweep, will sing

when Caesar marches the fierce Sygambri down

the Sacred Way, adorned with a ravishing 35

laurel crown—

never did fate or the gods in days of old

bestow a better or greater gift on men,

nor will they ever, not if the age of gold

comes back again— 40

you’ll sing of the public games and festivals

held when our gallant Augustus has returned,

granting our prayers; of the forum’s empty stalls

and courts adjourned.

Then I, if I can say anything worthwhile, 45

will join the crowd and shout in the words that come,

O shining sun! Praiseworthy one! and smile

that Caesar’s home.

While you pass by, we’ll cry to you more than once,

io triumphe! and all of Rome will cry 50

io triumphe! and burn sweet frankincense

to the gods on high.

You’ll sacrifice ten bulls and as many cows;

a fresh-weaned calf raised freely on a teeming

expanse of grasses will satisfy my vows, 55

tender and beaming

where horns about to sprout imitate the glowing

flames of the crescent moon on its third night;

the rest is tawny, but there, there’s a spot showing

of snowy white. 60