In the first two parts of this series, I wrote about my approach to varying the “sound” of my translations by making adjustments to form, diction, and syntax, and then about using different kinds of rhyme to vary the sound of four poets (Alcaeus, Sappho, Catullus and Horace) within one specific stanza (a version of the Sapphic).

Here I’d like to stick with Catullus and Horace while returning to the theme of nightingales for a sort of coda. I’m going to quote two poems, both of which are examples of the genre of the recusatio or “refusal” poem common in Augustan poetry. Apparently the poets around Maecenas were frequently being asked to tackle projects they didn’t fancy, and developed plenty of tactful ways of saying, “Thanks, but no thanks” to maintain their independence while still slipping in plenty of praise of their powerful patrons; Horace’s “Pindar” ode is one example I’ve already discussed.

As with much of later Roman poetry, Catullus may have had a hand in formalizing the technique, which was less of an established reflex for his generation (he died a decade or so before Julius Caesar). In poem 65, Catullus responds in epistolary form to a well-known orator and rival of Cicero’s, Quintus Hortensius Hortalus, who appears to have asked him for a poem he felt unable, for reasons the poem will make clear, to produce. Nevertheless, he was able to complete a translation of Callimachus’ (‘Battiades’) Lock of Berenice, which he enclosed preceded by the following lines:

Catullus 65

Etsi me assiduo confectum cura dolore

sevocat a doctis, Ortale, virginibus,

nec potis est dulcis Musarum expromere fetus

mens animi, tantis fluctuat ipsa malis—

namque mei nuper Lethaeo in gurgite fratris

pallidulum manans alluit unda pedem,

Troia Rhoeteo quem subter litore tellus

ereptum nostris obterit ex oculis.

* * * * * * * *

numquam ego te, vita frater amabilior,

aspiciam posthac? at certe semper amabo,

semper maesta tua carmina morte canam,

qualia sub densis ramorum concinit umbris

Daulias, absumpti fata gemens Ityli—

sed tamen in tantis maeroribus, Ortale, mitto

haec expressa tibi carmina Battiadae,

ne tua dicta vagis nequiquam credita ventis

effluxisse meo forte putes animo,

ut missum sponsi furtivo munere malum

procurrit casto virginis e gremio,

quod miserae oblitae molli sub veste locatum,

dum adventu matris prosilit, excutitur,

atque illud prono praeceps agitur decursu,

huic manat tristi conscius ore rubor.Though constant grief confounds me and its fetters,

Hortalus, keep me from the Maids of Letters,

and though my mind and heart are weak to press

the Muses’ fruit, still drowning in distress—

for recently my brother wet his toe,

death-pale, in turbid Lethe’s sluggish flow,

and took Rhoeteum’s Trojan dirt for pall,

ripped from my eyes by scanty burial— …

dear brother, dearer to me than life, will I

never see you again? I’ll always love you, 10

I’ll always make sad music because of you,

as Procne in the shade trees sings her pain,

mourning for Itylus, so early slain.

Yet, Hortalus, despite my grief, I send

lines of Battiades to you, my friend,

so you won’t think your plea, cast to the wind

in vain, has tumbled headlong from my mind

the way an apple, the hushed gift of a lover—

when the girl jumps at the entrance of her mother,

forgetful, poor thing, it was in her clothes— 20

spills from her virgin lap, and, as it goes

rolling away now in a headlong streak,

a guilty blush suffuses her sad cheek.

Unlike the coy excuses generally offered by Propertius and Horace, Catullus has refused Hortalus for a more convincing and sympathetic reason: his brother’s recent death (memorialized movingly in poem 101 as well) makes it impossible to concentrate on new writing, though apparently he can still translate out of Greek. He apostrophizes his brother in a moving aside, invoking the myth of Procne and her sister Philomela. Catullus has it that Procne, after killing her son Itylus (elsewhere, “Itys”) to punish her barbarous husband Tereus, was turned into a nightingale, whose song is thus a mournful complaint for what she did and suffered. (In Ovid’s more elaborate telling, Philomela turns into a nightingale, while Procne becomes a swallow and Tereus a hoopoe; this is the version to which the Wasteland famously alludes: “So rudely forc’d. Tereu.”)

I’ll always love you, 10

I’ll always make sad music because of you,

as Procne in the shade trees sings her pain,

mourning for Itylus, so early slain.

The most interesting part of the poem, however, comes in the simile with which it concludes, where Catullus compares himself to a girl embarrassed that her crush has been discovered by her mother on finding the apple her lover had given her (ll. 18-23):

ut missum sponsi furtivo munere malum

procurrit casto virginis e gremio,

quod miserae oblitae molli sub veste locatum,

dum adventu matris prosilit, excutitur,

atque illud prono praeceps agitur decursu,

huic manat tristi conscius ore rubor.the way an apple, the hushed gift of a lover—

when the girl jumps at the entrance of her mother,

forgetful, poor thing, it was in her clothes— 20

spills from her virgin lap, and, as it goes

rolling away now in a headlong streak,

a guilty blush suffuses her sad cheek.

In this simile, the syntax feels slightly like a Rube Goldberg machine, as the malum drops slowly and inexorably from one line to another, though the real poetic power is in the hustling juxtaposition (even callida iunctura) of the verbs prosilit, excutitur (whose subject is quod), followed by prō / nō prǣ / cēps ă gĭ / tūr dē / cūr sū, the slow spondaic ending of which carries a feeling of inevitability. The greater part of these effects relies on Latin word order—especially the ending on rubor, the redness of the blush matching that of the apple—and is thus out of the reach of the North American mockingbird; though my version does try to contrast the closed couplets of most of the poem with the more open and enjambed couplets in the simile, that initiate a different kind of movement and send the apple rolling unstoppably away.

Here is a second, much lighter-hearted recusatio, which catches the more bantering tone with which Augustan poets often invested the trope. Here Horace sends excuses to Maecenas about why he has not yet completed his book of Epodes:

Epode 14

Mollis inertia cur tantam diffuderit imis

oblivionem sensibus,

pocula Lethaeos ut si ducentia somnos

arente fauce traxerim,

candide Maecenas, occidis saepe rogando:

deus, deus nam me vetat

inceptos, olim promissum carmen, iambos

ad umbilicum adducere.

non aliter Samio dicunt arsisse Bathyllo

Anacreonta Teium,

qui persaepe cava testudine flevit amorem

non elaboratum ad pedem.

ureris ipse miser: quodsi non pulcrior ignis

accendit obsessam Ilion,

gaude sorte tua; me libertina, nec uno

contenta, Phryne macerat.What is this limp lethargy of limb

that blunts my every whim,

heedless, as if with parched lips I'd drunk deep

goblets of Lethe's sleep?

Maecenas, you’re killing me with all this nagging.

God, god is why I’m lagging!

A god keeps these (long promised, long impending)

epodes from their ending.

Bathyllus burned Anacreon, they say,

with love in this same way, 10

who often, on the lyre he carried with him,

complained in a singsong rhythm.

You're burning, too; but if your gorgeous toy

shines like the torch of Troy,

congratulations. Freed Phryne makes me suffer,

whom one man’s not enough for.

Naturally, I am once again using rhyme to try to catch Horace’s jocular tone: nagging / lagging; with him / rhythm; suffer / enough for. However, the real reason I quote this poem is for those first four lines, in which I hope you might hear a poem of rather greater stature:

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

I’ll end now by quoting from my end-note on Epode 14:

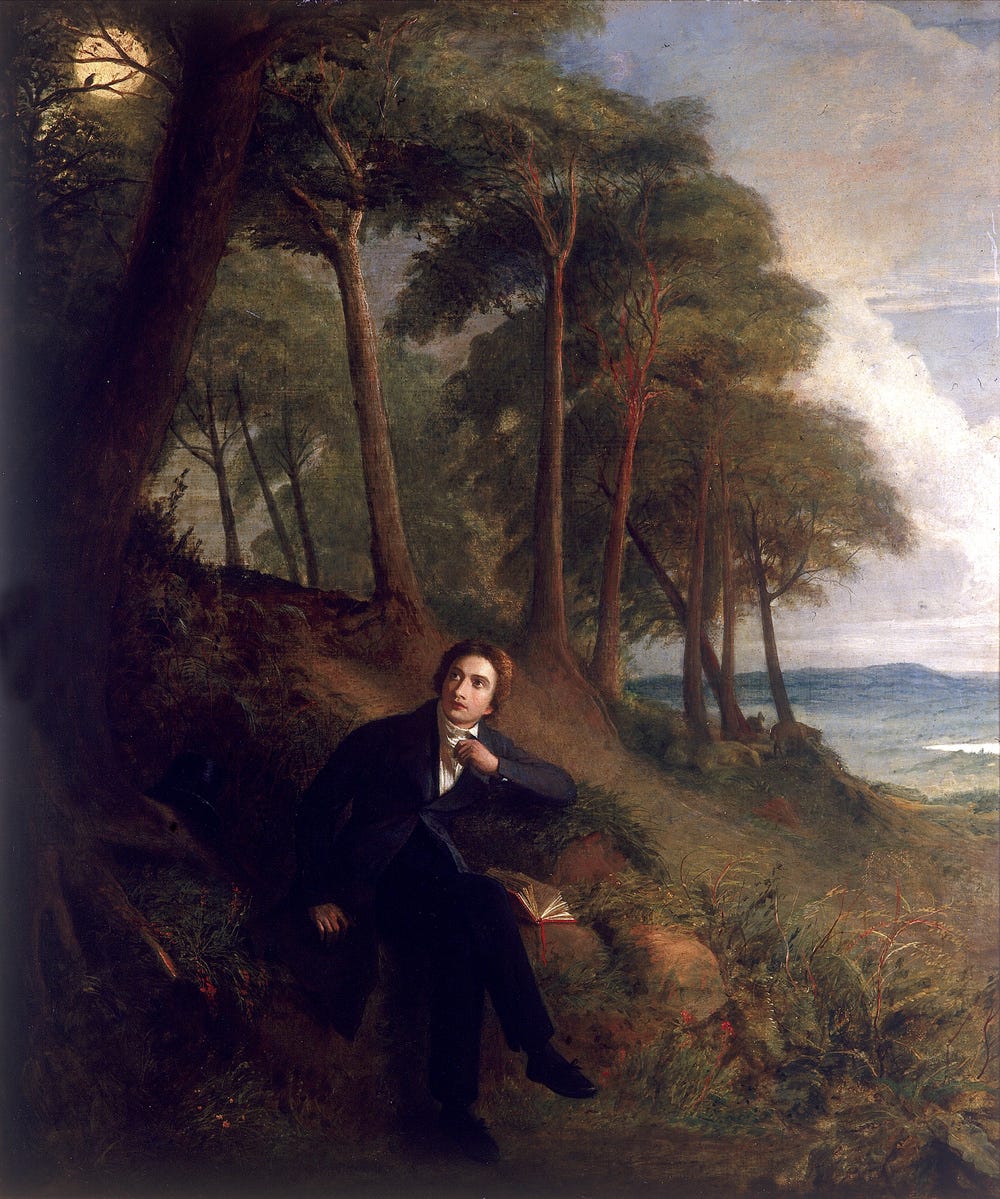

In 1929, Edmund Blunden thought it likely enough ‘that Keats had his Horace in his hand that day when he sat under the plum tree at Lawn Bank, and presently began to write’ his ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ (‘Keats and His Predecessors’, London Mercury 20, 1929, p. 292). In Horace’s epode, there is a conspiracy of lethargy and Lethe, torpor and forgetfulness, which both impedes and provokes poetry – one thinks of Keats’s celebration, in his letters and his verse, of ‘delicious diligent Indolence’. Horace’s poem is a variation on the recusatio. Catullus 65 plays on similar themes. In that poem, Catullus compares his own music to the nightingale’s. Keats also lost a brother at an early age; he, too, was obsessed with the great poem he should have been writing (he thought of his odes as minor works). At any rate, in transmuting these two little Latin poems (Horace’s is just a squib) into one of the great lyrics of English literature, Keats used the Romans exactly as they used each other and the Greeks before them – including, of course, Callimachus, whose reference to the poems of his dead friend Heraclitus as ‘nightingales’ (Epigram 34) may also have been fluttering somewhere in Keats’s brain that April of 1819.

If one is to draw any lesson from the attempts at transmutation I’ve been presenting, in this poem and others, it may be that, in every poetic nightingale there is at least a little bit of mockingbird.

Wonderful exposition of classical poetry reverberating through time. Thank you.